What I Learned in a Logging Camp

A man who stole a million dollars worth of gold sees God in a sunrise

Don’t stick your finger down a seagull’s throat

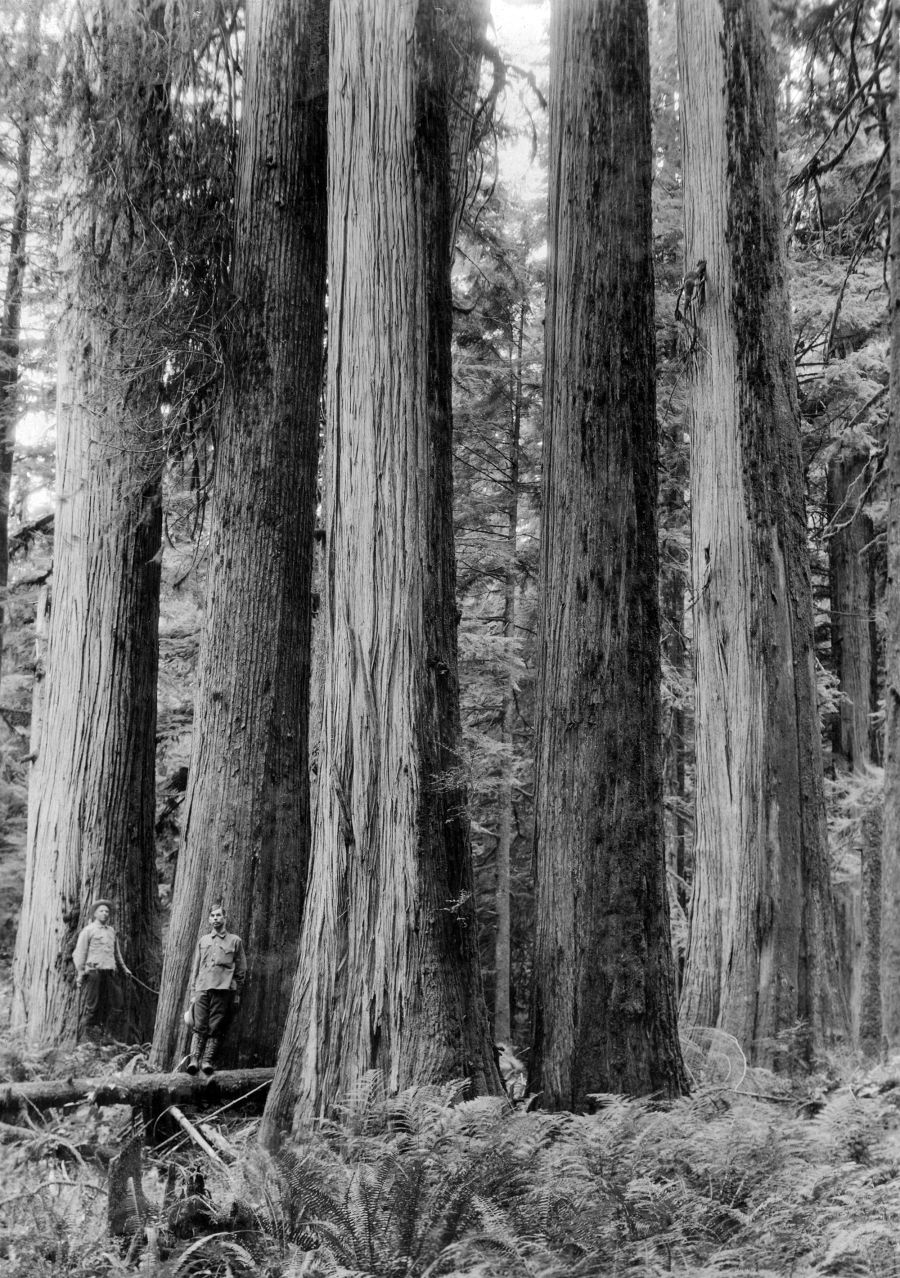

My first job, where I was expected to do a man’s work, was in an isolated logging camp, on the far west coast of Canada’s Vancouver Island. There the constant wind and perpetual rain produced giant trees, the oldest of them 1,000 years old, Sitka spruce and Douglas fir topping 300 feet tall and 30 feet in diameter. These first-growth giants grew on precipitous hillsides — inaccessible to previous generations of loggers, but not to us, thanks to a recent innovation, the now long-outdated tracked steel spar yarder.

The camp itself, where 40 to 50 men slept and ate, was a cluster of modular bunkhouses, a few scattered, primitive, 2-bedroom bungalows for favored staff and, at the end of a dock, the cookhouse, which was set on floats. That’s where the seaplanes docked. Two large diesel generators ran night and day.

There was no way in or out of the camp except by biweekly supply boat, the company seaplane, or a costly chartered aircraft. Our camp was a “highball outfit” which meant we operated seven days a week, 12 hours a day. After six weeks of this brutal regimen, the logging company would fly a man out for 10 days off; which most of us were unable to handle. Loggers returning from town were as unstable as old dynamite until reaccustomed to the bloody drudgery of camp routine.

There were no roads in the logging camp except those we built ourselves. These snaked from the sheltered sea level camp up the wind-whipped ridges of the rounded hills of Cascadia’s coastal range. Up around and across, to wherever the great stands of giant fir, spruce, and cedar grew.

Mel the driller, a catskinner, and myself would leave a wide spot on the road every quarter mile or so. That’s where the tracked steel spar yarder would later plant its hydraulic feet, and where the logs it yarded off the sidehill were stacked, prior to being grapple-loaded on logging trucks and hauled two to 10 miles to the self-loading and dumping barges docked in Malksope Inlet. The barges would transport the logs to the sawmill town of Tahsis. A company town, Tahsis was owned by our ultimate employer, the King of Denmark, via the East Asiatic Company.

The first thing I learned from Mel the driller was that wrapping dynamite casings around the sweatband of a hard hat, or any hat, will produce a blinding nitroglycerin headache. Should the Superintendent continue to ask about our missing chainsaw, such a tactic might be used to distract him, Mel suggested. I couldn’t tell if he was joking or not.

The missing chainsaw had been run over by the catskinner, in the D9 bulldozer with which he cleaned up after our “shots,” as blasts were known, and who kept our roads on grade.

The destroyed saw, or parts thereof, had been buried in a culvert a mile behind us on the road several weeks ago. Now, the Superintendent kept asking where the missing chainsaw was. In the end, someone dug up the wrecked chainsaw and Mel laid out the twisted bar, the magnesium engine block, and other bits and pieces on a stump, where the Superintendent would see them on his next visit to the job site.

In due course, after the Superintendent clocked our progress on the road, he prepared to depart. “We found that missing chainsaw,” said Mel, as the Superintendent got in his truck.

“I saw that, Mel,” said the Superintendent. He glared at us all, slammed his door, and drove off. We reburied the chainsaw and never mentioned it again.

Mel the driller taught me something else. We had a one-legged seagull, a pet, who hung around the cookhouse float. “A seagull has the most powerful stomach acid in the world. It liquifies fish bones,” said Mel. He claimed to have won a thousand dollars from a faller, betting the man couldn’t hold his finger down a seagull’s throat for one minute.

Mel loved recalling this event. I can still remember the look of pure delight on his face as he told how the faller reached five seconds, started sweating, his moan turned into a scream and he jerked his finger out of the bird’s throat and stuck it in a glass of milk.

Mel had a lot of stories, but I looked it up and it is quite true: A seagull’s stomach consists of two chambers. The first the proventriculus secretes a powerful acid and is best developed in birds that swallow entire fish, i.e. seagulls.

Mel was a master driller. He could, by placement of bore holes in the rock strata at different depths and in surprising patterns, and then by packing the holes with dynamite and ANFO, timing the sequence of borehole explosions with detonating cord, measured only by eye, lift huge masses of shattered rock and place them anywhere he desired, with any degree of required fragmentation, from pea gravel for surfacing roads to house-sized boulders to shore up steep drop-offs.

Mel had learned drilling and blasting underground in the hard rock mines of North Ontario and Canada’s Northwest Territories. He showed me, lifting his battered hard hat, how his hair had turned entirely white on one side of his head. This was the result, Mel said, of being trapped for five days underground, licking rocks for water, drinking piss, and not knowing if rescue was possible. When he was rescued Mel swore he’d never go underground again and he never did, at least not until he died.

Mel told me he’d worked in a gold mine once, a rich one, outside of Yellowstone in Canada’s unutterably forlorn Northwest Territories. The gold at the gypo mine ran in strips through the quartz, and it glittered in the shattered rock after Mel’s shots. The fast-buck mining company, as customary in such conditions, strip-searched every miner coming off shift, particularly drillers, who had the earliest and best opportunity to steal pure gold from the company quartz.

Mel stole gold, for that was the custom then too. Not so dumb as to risk arrest or being beaten to death privately by angry employers, Mel put the gold he stole in a canvas sack which he then placed in a 50 lb. bucket and lowered down an unused shaft. Mel ruefully admitted he’d never had an opportunity to retrieve the stolen gold, and now it was too late. He’d checked, Mel said, the mine had been sold a few times, was now abandoned, and, he believed, flooded.

Mel didn’t recall precisely how much gold he’d stolen. About 42 lbs., he estimated, over the year or so he worked there. At a current cost of $23,000 or so per lb., Mel’s hoard would be worth approximately $966,000 dollars today.

One day Mel and I sat on the drill rig, drinking coffee from our thermoses and watching the sunrise — a rarely-seen event. “Do you believe in God,” Mel asked?

Without waiting for an answer, he continued, “They say He was all alone up there for a while, well. He must’a been a lonesome cocksucker and where’d he come from?”

Mel was a man who could call God a cocksucker, without the slightest ill will, much sympathy, and some sadness.