Jesus Christ is Born in Texas

70,000 believers arrive at the Prestonwood Baptist Church in Dallas to witness America’s greatest Christmas pageant

The ‘Gift of Christmas’ has production values that equal Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour

A journey to the heart of the American religion

94.9 KLTY FA-la-LA-la-LA The REAL Christmas Station it’s Bonnie and Jeremiah in the morning oh my goodness Bonnie I almost said Jonnie and Beremiah in the morning! Oh my goodness! We need a name! A couple-name! Jeremonie? Beremiah? Beremiah! Ha! Ha ha! Well Merry Christmas Dallas! Merry Christmas Fort Worth! It’s Beremiah in the morning! That’s right and if you like encouraging, inspiring Christmas music — I know I do! — Well we play it on KLTY all season long — that’s right — and if you want to keep hearing encouraging, inspiring music all year long stick around after we put the decorations away and stay with us because that’s what we do we celebrate encouraging, inspiring, hopeful music and we’d love to share it with you.

Andy Pearson is sitting in the sixth row at Prestonwood Baptist Church. He is staring at an empty stage. He is trying to concentrate, to envision how this vacant space will be transformed by the sudden appearance of the savior. Even for a faithful man like Andy, it can be difficult at times to believe. There are simply too many things that could go wrong.

There is, for one thing, the traffic: It has been 24 years and 25 days since Texas’s motorways last failed to kill a motorist between sunup and sundown; an 8,791-day killstreak. Today, it could claim any one of his thousand cast members who drive over the bone-white highways connecting Duncanville, Grapevine, Garland, McKinney, Wylie, Frisco, Allen, Arlington, Euless, Corinth, Combine, Hendrix, Hutchins, Greenville, Benbrook, Sunnyvale, Irving, Prosper — the entire Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex — to the 140-acre Prestonwood spread, God’s blessing to Plano. There is, for another thing, a stomach bug going around in Sunday school, which might render a good chunk of his 350 little extras down for the count on opening night. Then there are all the animals — the horses, donkeys, sheep, peacocks, zebras, alpacas, and dromedaries. There’s the baby elephant who once unleashed a stream of hot piss, right before the number where the little shepherds knelt on the plywood.

I imagine Andy is trying not to think about those wet little shepherds. He is trying not to think about all the things he can’t control: the lights, sounds, and pyrotechnics; the axles on the 20-year-old chariot that will bring in the magi; the frame on the 100-year-old sleigh that will carry his boss’s wife offstage after her “White Christmas” solo. He is trying not to think about the four flying elves, five flying drummer boys, and six flying angels, any one of whom might accidentally send a slipper or a drumstick or a crown plummeting down onto the head of some unsuspecting congregant. What Andy is trying to think about are the 70,000 people who, over the next two weeks, will come by plane and bus and car, from as near as Hebron and as far as Quito, to witness the Gift of Christmas — a three-act choreographed musical production involving nearly a thousand volunteer performers that for the last thirty years has set the mark of excellence in stage production throughout the Christian world. And to meet that standard of excellence, Andy Pearson must believe.

We’re at T-minus 81 hours and 16 minutes till opening night. Blocking begins at 6:00 PM sharp this evening. Dress rehearsal is tomorrow, so cast members are not expected to arrive today in their nativity costumes — their “biblicals.” But this is still a full run-through of the big one, the final number, when well over two hundred choir members dressed in bedouin garb descend from the wings of one of America’s largest sanctuaries carrying lit candles, singing “Noël” before ending with “O Holy Night” — and Andy expects everyone to be on their A-game.

As Prestonwood’s creative director, Andy has personally overseen nearly three months of weekly rehearsals since auditions began in September, though hardly without support. His fellow staff members are all drawn from the most elite ranks of the evangelical entertainment universe. Together, they constitute an A-team of born-again troubadours: Larry Brubaker, the orchestra conductor, grew up down the road from gospel-legend Bill Gaither; he went on to become the band leader for Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker’s megapopular The PTL (Praise the Lord) Club, the evangelical answer to Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show. Jonathan Walker, who arranged the show’s music, learned the trade at Cross Church in Arkansas (weekly attendance: 9,156) and now commands the Prestonwood Choir, one of the top choral programs in the country. Bryan Bailey, a.k.a. @worshipmediaman, Prestonwood’s audio-visual whiz-kid, has earned Gift of Christmas feature stories in leading AV industry mags, and his posts of Prestonwood’s media ops garner millions of views online. And then there’s Andy himself, who cut his teeth as a child star under the showlights of Branson, where he dropped out of high school to direct and produce shows at Silver Dollar City, before becoming the youngest choreographer in the history of Country Tonite — the most awarded show in the nation’s most competitive market for faith and family entertainment.

These words might not mean anything to you, but for millions of American evangelicals, you can safely be assured, they are a very, very big deal. The weekly Sunday services these men help produce — not to mention the many records, choir tours, conferences, and mission trips they organize — are scrutinized by pastors across the country who model their own ministries after Prestonwood. Step into any evangelical church in America on any given Sunday and you might hear a choir song that Jonathan arranged, see a transition sequence that Bryan designed, or behold a musical number that Andy choreographed. They are not miserly with their success. Everything they do is for The Kingdom, which is a place that is not of this world but that is nonetheless sought after in its absence: a sanctuary even bigger than this coliseum in Plano, where everyone who accepts the invitation can find a seat.

“Kingdom Work” is what they call it — this daily grind to turn a two-thousand-year-old story about a Jewish rabbi crucified by the Romans in Judea into a two-hour showstopping musical — and it is the burden of this work that weighs upon Andy’s shoulders. Back in his office, his crystal blue eyes look out under a flat-brimmed ballcap as he prepares for tonight’s blocking. He pensively scratches a neatly trimmed blond soul patch that punctuates a tanned and striking jawline. In matching athleisure and sneakers, he looks less like a dancer than a pro golfer, but on stage he is grace in motion. He has half a dozen numbers of his own to rehearse — from a ballet-inspired interpretive dance of the first chapter of Genesis to a turn in the Santa suit during an upbeat rock ‘n’ roll section.

As he sits behind the thick slab of his reclaimed wood desk, he allows himself to stick his head above the current for a bare moment and look back at how far he has come. He grew up performing in Prestonwood’s children’s ministry before his family moved to Branson, where his talents quickly brought him into company with the town’s crepuscular legends, like Ed McMahon and Andy Williams. The list of straight Baptist male choreographers is short, so when Prestonwood went searching for one to revamp their Christmas show, Andy’s age was no impediment. At only 18, the church began flying him out ten to twelve weekends every fall to set up Gift of Christmas. He’d stay in Plano for 24 hours before being shuttled back to Branson. Four years of that, fourteen shows a year.

“There was all this stuff happening, but at the end of the day I knew I wanted to have a family,” Andy said. “I love Jesus. I was so intrigued by arts and church, but I didn’t understand how my professional world and ministry could ever connect.”

Then he went on a mission trip. England. Kind of a strange place to share the light of the world, seeing as it’s the flame from which our city on a hill was originally lit, but this was a different song and dance from the standard jungle mission to save bare-breasted heathens. It was four weeks of sharing the largesse of American evangelicalism to doddering congregations in working-class English towns, distributing food by day and performing a high-octane gospel show by night.

“And the Lord put it on my heart: Arts is the hook. Share Jesus with as many people as possible and use arts as the vehicle.”

At 5:45 PM, Andy looks up at a backstage monitor to see senior choir members filtering in from the early winter sunset. They gradually find seats in the sanctuary’s pews of polished wood and tufted emerald upholstery, their footsteps muffled by a thin layer of matching green carpet. The women are thickly perfumed, many of the men in jacket and tie. They do not savvy the younger generation’s habit of casual church wear. They smile magnificently as they greet one another, reaching out, grasping hands. They have spent the day feeding grandkids home from college and quilting blankets for newborns, singing quietly to the CD that has been playing on repeat in their kitchens since September — born this happy morning.

Andy heads back to the sixth row, watching keenly as the choir’s chatter fades to a pregnant silence as everyone finds their places in the sanctuary’s wings. The house lights are turned all the way up so every gesture, every face can be analyzed. It’s the last chance to tighten the screws before tomorrow’s dress rehearsal, and right now you can see Andy Pearson’s scythe-like focus glint in the overhead lights. This is what Prestonwood pays him for. He’s raised up this group from tender shoots and now it’s time to separate the wheat from the chaff.

Queue the music. Candles. Choir: The first Noël the angel did say / Was to certain poor shepherds in fields as they lay.

As the song progresses, the choir moves slowly towards the stage from the wings on both floors of the sanctuary. The goal here is to overwhelm the audience with candlelight, impressing upon them the universality of hope born two thousand years ago in Bethlehem. While the actual show will include hundreds of marvelous trappings that the pilgrims can ooh and aww at, tonight the actors face a predicament akin to performing in front of an enormous green screen. The choir pours through the sanctuary’s doors, pointing to the empty stage in mock wonder, looking around the vacant seats with reverent stares. They tap one another on the shoulder, urging the other to see what cannot be seen. Heavenly hosts dart invisibly above them, and they twirl their heads around in witness. Though each of them sings, it is impossible to hear anyone above the roar of the prerecorded vocals. They cannot hear their voice for the sound of their own voice; still, a few choir members lift their hands in genuine gestures of worship, closing their eyes against the glare of the stage lights. When the song finishes and they find themselves gathered together on stage, they gaze at one another in genuine surprise, wipe real tears from their eyes, and clap for themselves.

“Alright, great, a few notes.” Andy stands before anyone has time to move offstage. “Sing more. Act more. It looked a bit like a high-school graduation up there. I think that if you were actually at Bethlehem you would not have been standing still.”

He pauses and looks down at his notepad. “Okay, honestly, it was a pretty good job on the entrance. But we’re going to run it back. We’re not going to go all the way back. We’re just going to go back to Angels and run Angels through the end one more time. Okay? So we’re not running Marketplace. We’re not running Mary and Joseph and Gabriel. We’re just gonna start from Angels and roll back through. Got it?”

Not a murmur, not a whisper, not the faintest sigh of disappointment can be heard. Even still, Andy softens his voice in sympathy.

“I know it’s a lot, but remember: Your sacrifice here matters for eternity. People’s eternal fate will be impacted by what you do up here in the next few weeks. Anyone that’s bought a ticket, that’s coming here to see what we do, we know it’s no accident. It’s anointed… Amen?”

Amen. The choir returns to their positions, and again they filter in, spread apart, come together, sing, pretend to sing. See two of them find each other in the crowd, resplendently silver-haired, dressed in pink cashmere scarves and knitted turtlenecks, moving indelibly towards one another, pointing, marveling at unknown things overhead. Pretending, pretending to pretend; they bow their heads and lower themselves onto a knee, as though for all the world tonight they are kneeling before the throne in Bethlehem.

Even among believers, Baptists stand out for their belief. Their name derives from their practice of the believer’s baptism: immersion in water, which demonstrates one’s belief in Christ rather than one’s institutional affiliation with a church. This made it distinct from infant baptism, a nearly universal practice among all Christian denominations, from Roman Catholics to New England Puritans, prior to the English Separatist movement in the seventeenth century. Infant baptism was typically done by sprinkling or pouring water over the head of a child, and it was a sign of a family’s covenant with God and their commitment to the church that administered it. But it had weak basis in scripture, and under the lens of John Calvin’s new, strict theology of salvation, it presented a hair-raising possibility: a person receiving the sign of God’s blessing who was not a member of God’s elect.

For some of the most radical thinkers of the Protestant Reformation, infant baptism amounted to heresy because it signified God’s blessing upon children before they could testify to their faith in God’s grace, and so some extremists began to baptize only those who could profess belief, immersing them in rivers and lakes just as John had dipped Christ into the Jordan. The first generation of these radicals were based in Switzerland and known as ana-baptists — literally “baptized again” — because a believer’s baptism was usually the second they had received. But as their English counterparts fled from monarchy to the New World, and then fled again from the New World’s burgeoning theocracy to the godforsaken expanses of the frontier, they became a people who did not define themselves by what had come before but by a conversion experience which revealed the light of what was to come. In America, there were no second-baptisms, no ana-baptists. There was only one kind of true baptism — a believer’s baptism — and there was only one kind of true believer: a Baptist.

In Dallas today there are Baptists everywhere, but this was not always the case. The earliest Christian influence in Texas came from Catholicism preached by Spanish monks, whose missions seem to have taken root less in the state’s eastern half than in the austere badlands out west. In 1834, the preacher Daniel Parker led a caravan down from Illinois to hold the territory’s first Baptist service. When they arrived they found mostly untamed floodplains, flat as a board, and when they stuck their white cross into the dank earth they planted a seed that would grow like bastard cabbage over the Texas landscape. Parker was what is now known as a primitive baptist. In his time, his particular doctrine was called by many names: Square-Toed, Broad-Brimmed, Old-School, Hard-Shelled, Old-Fashioned, Hard-Rined.

Parker wore the hairshirt of Calvinism without apology, and he held firm to the doctrine of predestination — the belief that God has preordained people for either heaven or hell, and no amount of mothers’ prayers can do a thing about it. That stubborn belief made Parker indignant at fellow Baptists who formed mission societies to preach to what he believed were irredeemably fallen heathens, like Indians or Catholics. Not only did Parker find such efforts futile, he resented the mission societies — funded by Baptist universities like Brown in the east — which claimed authority in the training and education of men for the ministry. For frontier Baptists like Parker, such organizing bodies were little more than finishing schools for modern-day Pharisees. While his theology would prove too strict to become popular, Parker’s distrust of formal education would prove to be a widely held sentiment in Baptist culture, summed up pretty clearly 160 years later by another Texas Baptist named Willie Nelson: “If you can’t preach without going to school, then you ain’t a preacher / You’re an educated fool.”

In Parker’s dispute with the liberal impulses of mission societies, one can trace veins of a fracture that runs through the entire history of American Christianity. The term “Baptist” has never signified a single, strict collection of beliefs. As a result, Americans who want to understand Christianity — particularly what is referred to as evangelical Christianity — need a different vocabulary than “Baptists” and “Methodists” and “Presbyterians,” or even “fundamentalist” and “progressive.” The denominational boundaries churches use to define themselves are no more historically permanent than the four corners of a revival tent show; but there are tectonic forces that shape American Christianity, and a more geologic study is needed to discern these variable movers of faith.

The trained eye can detect these forces on an ordinary Sunday at Prestonwood. Newcomers who arrive early will find a dozen spaces at the front of the parking lot reserved for “First Time Visitors.” Upon walking in, someone at the door will warmly greet these new arrivals and, having clocked their parking spot, will direct them to an usher who can make sure they get a good seat. When the worship service starts, giant screens flanking the stage project lyrics so that everyone can sing along. First-timers will find the music totally accessible: The genre, known as Christian Contemporary Music, derives much of its sensibility from stadium-rock bands of the 1980s, with a penchant for four-bar choruses and big, powerful bridges. At large churches in metropolitan cities like Dallas, both genders and most races will be represented onstage.

After the worship music ends, the ordinary audience member ought to feel wholly welcome — should feel, in fact, that the entire facility of the church has been designed to meet their needs. Nothing they have experienced, as a first-timer, will be able to tell them conclusively that they are in a conservative Baptist or progressive Presbyterian or liberal Methodist church. By virtue of its attention to a newcomer’s comfort, however, Prestonwood has signaled its strong affiliation with revivalism, a lesser-used term among the secular public which basically refers to a church’s desire to create moments of spiritual awakening that will earn it new converts. Revivalism is the opposite of what might be called covenantry — a church’s desire to create the holiest community possible. A Cistercian commune is covenantal; the Amish are covenantal. The ordinary American would feel out of place among both. New England Puritanism was also covenantal; and likewise would the estranged English yeoman, German immigrant, or, needless to say, town-drunk feel acutely unwelcome stepping into a Sunday service in Plymouth.

Hence why early America was fertile ground for revivalism. Beginning with the First Great Awakening of the mid-eighteenth century, which flourished around the New England hinterlands, and extending through to the mid-nineteenth century with the Second Great Awakening, which reached out to the frontier west of the Alleghenies, revivalist preachers pitched tents in fields and perched on soapboxes in brush arbors to proselytize with a simple message of salvation to lonely people who, by virtue of geography, identity, or temperament, had found themselves outside the fold of a covenantal community.

Spectacle always played a predominant role. Jonathan Edwards called his meetings “concerts of prayer”; his contemporaries called the movement he led the Great Noise. George Whitefield, the English preacher who set the Awakening in motion, was such a talented stage performer that David Garrick, the greatest English actor of his day, claimed the preacher could silence a crowd merely by speaking the word “Mesopotamia.” (By Benjamin Franklin’s calculation, Whitefield’s voice could reach some thirty thousand souls in a quiet field with little wind.) Charles Grandison Finney, a leader of the Second Awakening, was fond of cajoling congregants onto the “anxious bench” where everyone could witness the spirit move. Forty years later, Billy Sunday built temporary tabernacles the size of small villages and urged his audience to “walk the sawdust trail” to claim Christ right next to him on stage.

The spectacle of music or stagecraft not only served to entice outsiders but also created the conditions that would lead to a convincing conversion experience. The importance of this experience cannot be overstated. By far the most haunting concern of any Christian since the Protestant Reformation is assurance: the question of whether or not one is truly saved. In a covenantal community, like much of pre-Reformation Europe, assurance was settled simply by belonging to the One True Church — Roman Catholicism — which was typically the only game in town. In the chaos of America, however, where competing faiths soon lined every corner, the problem of assurance had to be assuaged by what revival preachers called “experimental religion.” This was a faith born from a singular conversion experience that a believer might rely on throughout his life as ballast against doubt. It might be as earth-shattering as a vision, or as simple as a tingle up the spine. Whatever it was, it served as quasi-empirical proof of miraculous salvation for people living in an increasingly chaotic, empirical world.

As the music fades into the sermon, a newcomer at Prestonwood will likely be surprised to find that this church — which has a distinctly modern appearance — cares deeply about the old words of the Bible. Almost as soon as he is onstage, the preacher will present a selection of verses (also projected onscreen) before spending roughly half an hour parsing out the meaning of the words and their relevance to the story of Christ. Don’t let your eyes get lazy reading this. The second part of that statement is of vital importance: The point of the sermon is not to demonstrate how the Bible can help us live better lives, but rather how all verses reinforce the argument that Jesus Christ’s death and resurrection rescued mankind from sin.

Here the church reveals its relationship to inerrancy, which is the single most important point of reference for understanding American churches. Inerrancy refers to the belief that the Bible is without error. There are different levels of belief in inerrancy, from so-called “unlimited” inerrancy, which posits that the Bible is without factual error, to “limited” inerrancy, which posits that it is without error in regard to matters of faith. It’s worth noting that what counts as a matter of faith, versus a matter of fact, is highly variable among theologians. Even conservative theologians can grant some leniency with regard to matter of fact — such as the number of Philistines Samson slaughtered with an ass’s jawbone being a cool 1,000, if you take the writer of Judges at his word — so long as the fact does not constitute part of the inviolable chain that leads to Jesus’s death and resurrection.

The people who think the most about this stuff (they’re called “systematic theologians”) have determined that the most coherent way to hold a belief in inerrancy — particularly in unlimited inerrancy — is to read the Bible as being totally and completely written to support the argument that Jesus Christ died and rose again for the redemption of mankind. If you like Wittgenstein’s philosophy of language, Christ is the “rule” that organizes the “game” of scripture. Consequently, if you break the rule, the game no longer makes sense. Here’s how it works: If you believe not that it’s literally true that God created the world in seven days (Genesis 1:1-31), but rather that the creation story in Genesis is intended to be read as an ancient myth, then you will be open to the possibility that other parts of the Bible which are presented factually can be read metaphorically; if parts of the Bible can be read metaphorically, then Jesus’s statement that “I and the Father are one” (John 10:30) might be taken to mean that Jesus feels close to God, but is not actually God; if Jesus is not actually God, then his death and resurrection is not a sufficient sacrifice for our sins — but since Jesus’s death and resurrection is a sufficient sacrifice for our sins, thus it must be the literal truth that God created the world in seven days.

The whole matter of inerrancy was largely moot prior to the Enlightenment. It was only after someone could offer a plausible explanation for why the earth is older than 4,000 years that interpreting Genesis as factually faultless became meaningful. The theory of evolution and the methods of “higher criticism” (a kind of philological approach to the Bible) brought the debate to a rolling boil by the turn of the century, prompting the fundamentalist movement in American Protestantism (named after a series of essays in the 1910s defending inerrancy that were commissioned by the founder of Union Oil, collectively titled The Fundamentals). A church’s measure of belief in inerrancy soon became the quickest determinant of its politics; however, it would be inaccurate to equate inerrancy with conservatism. Arguably the most famous representative of Biblical inerrancy in the early twentieth century is William Jennings Bryan, who argued against evolution in the Scopes Monkey Trial whilst standing as a key figure in the Progressive movement.

Though it’s unquestionably true that inerrancy was wielded by Southern preachers to defend slavery and segregation, it’d be difficult to find a Southern Baptist preacher today who believes either practice — at least in the modern American context — is justified by scripture. Generally speaking, Biblical inerrancy can take a classic liberal right up to about 1965 — but not a step further.

While Baptist leaders had debated inerrancy since the 19th century, it was only after the Civil Rights Era that the issue became a matter of paramount concern for the everyday American churchgoer. Each of the three most prominent denominations of American Protestantism — Presbyterians, Methodists, and Baptists — has effectively experienced some kind of schism over these issues in the years since 1965. That’s because on the social issues that mattered most during this era — abortion, gender and racial equality, gay rights — an inerrant view of the Bible did not support a progressive position. No single moment illustrates the crisis better than the 1985 Southern Baptist Convention, when leaders of the largest evangelical denomination in the country gathered at the Dallas Convention Center to determine whether convention members would follow a moderate or strict view of inerrancy. Over forty-five thousand people showed up, doubling the previous attendance record, plus nearly six hundred reporters. Those with the strictest view of inerrancy carried the day.

Thirty miles north, the results of that vote can be felt at Prestonwood. As the newcomer settles down from the worship music and listens to the sermon, they will notice that it is building towards a moment in which they will be asked to participate in the service, not merely by placing a check in a basket or drinking a Dixie Cup of grape juice, but by making a decision that will affect the eternal ledger of human souls. This moment is historically known as an altar call, but at Prestonwood it is called Invitation: a chance for nonbelievers to accept Jesus as their Lord and Savior.

Invitation signals Prestonwood’s strong revivalist and strict inerrantist views. Note that these two variables are independent from each other: There can be strong revivalist but weak inerrantist churches — like the Hillsong megachurch — and weak revivalist but strong inerrantist churches, like Daniel Parker’s primitive baptist church. But the strong revivalist, strict inerrantist style is the combination that has come to dominate American evangelicalism, and it is what tends to be referred to when op-ed writers paint, in characteristically broad strokes, the “evangelical” or “fundamentalist” or “Christian nationalist” community.

What truly distinguishes these Christians in modern society is not politics, however. It is belief. In a world of doubt, they believe. Prior to the advent of modern historical criticism, belief itself was a largely irrelevant facet of faith. As the historian Wilfred Cantwell Smith argues in his book Believing:

The affirmation “I believe in God” used to mean: “Given the reality of God as a fact of the universe, I hereby pledge to Him my heart and soul…” Today the statement might be taken by some as meaning: “Given the uncertainty as to whether there is a God or not, as a fact of modern life, I announce that my opinion is ‘yes.’”

When the earliest revival preachers perched on their soapboxes, they were not imploring men to believe in God as a fact of metaphysics, but to get right with a God they had abandoned for the sake of wealth or pleasure, not unlike a spurned lover or friend. Of course, this was in itself a radical departure from previous notions of the divine. The beauty of the Great Awakening was that laymen began to seriously consider their personal relationship with God, a God who so loved them that He even followed them out to a frontier in which many sought to escape Him. It was this love that was at the center of the Baptist preacher’s message.

Love is still at the heart of the gospel, but faith requires something more from modern man than mere goodwill. You have to believe. For by grace you have been saved through faith, the apostle Paul wrote. Your good works are no longer enough. Through a glass in which we see darkly, you must for a moment behold the light.

KLTY you’re listening to the REAL Christmas station traffic update coming out of Wylie this morning as police investigate a big-rig crash that left one dead officers arrived on the scene to find a small Volkswagen wedged beneath an 18-wheeler so expect major delays we want to know what makes this time of year special for YOU so give us a call here at 888-949-KLTY and tell T-Lo what you’re feeling GOOD about during the MOST wonderful time of the year Hello you’re lucky caller number seven on KLTY the REAL Christmas station Hello my name is Charmaine Hey Charmaine! Hey. Charmaine tell us what you’re feeling GOOD about during the MOST wonderful time of the year ok what I’m feeling good about this Christmas is baking everybody’s favorite pie which everybody loves.

“Uh, sorry, I promise I’m not sick. I have, ugh, allergies,” Matt Webb says. “We have scent cannons this year. For the bakery number.”

Thirty-six years ago, Webb was baby Jesus in Gift of Christmas. He was probably a really cute kid. His babyface lovability is on full display as he turns the mic of his over-ear headset back to better reveal a hearty smile. Webb is now the head of the show’s production design. It is his job to take the showrunners’ creative vision and “run it through the machine of reality.” He got his start doing follow spots for the church as a teenager. Now he is head of lighting design on a show that runs as many as three hundred individually coded lighting queues in a single song.

On Friday morning, before dress rehearsal, he looks out from center stage over the vast expanse of empty seats, perfectly at peace. Around him scurry techies from nearly every walk of entertainment: pyrotechnics, high-fly installation and operation, graphics, sound design, animal handling, aerial performance, and costuming. NDAs mostly preclude the sharing of details about their other clients, but names that slip through in conversation reveal this is no crackerjack operation: Rihanna, Usher, Kid Cudi, Zac Brown, Bruce Springsteen, Google, Walmart. “I did screens for Slayer, Marilyn Manson,” the screens producer tells me. “Pretty different.”

A surprising number of these contractors, like Webb, got their start working in the booth at their local church, while many others have become regulars on the circuit of megachurch shows. “I started out with Peter Pan on Broadway. I used to work all those shows in New York,” a high-fly operator with a chopped mullet, patchwork tattoos, and floppy Doc Martens says. She speaks in the same reflective tone that a believer might use when sharing bits of a sordid past. Then she smiles. “But now I mostly work Jesus shows.”

Money talks, of course, and there is no indication that any of these hired guns are here out of the goodness of their hearts. Yet Prestonwood offers something else that is evidently rare in their line of work: No one bitches about their job. Stage hands are ordinarily some of the most irascible creatures on the planet; their entire conversational identity usually revolves around how many days in a row they’ve worked, how underpaid they are, and how under qualified everyone is (excluding themselves, of course). Here, however, the relentless joy of their clients seeps in. As Bryan Bailey, the media director, prays over the comms for these scallywags to be “conduits through which the holy spirit might move,” nary a snicker can be heard. Instead, it is answered by a resounding amen.

What makes this even more remarkable is that Gift of Christmas is likely the most inconvenient show they work all year. Unlike an ordinary Broadway show, nearly all of the cast members are unpaid volunteers, so all rehearsals must be crammed into evenings and weekends. The sanctuary, though gargantuan, was not built with theatrical production in mind, so all stage elements (including the dromedaries) must be able to fit through an ordinary pair of double doors in the lobby designed to fit no creature larger than an All-Pro linebacker, while the fly systems and orchestra pit must be built from scratch. Plus, there’s just the sheer scale of the thing.

“We don’t know of another show in North America that flies more performers,” Webb says. The screens guy nods.

“There’s no other place I’ve ever seen that has a stage this big. Maybe there’s something happening, you know, overseas that is bigger. I think Adele recently had a stage roughly this big. But nothing with this kind of depth. Unless you count, like, you know, Taylor Swift’s ego run,” he says, using the industry term for the phallic stage extension that protrudes out into an audience so that a popstar might “have all these people pour their souls out to her.”

“There’s no ego run here,” Webb says, grinning.

Brian Bailey is the only member of the show’s production team who can claim to have attained some measure of fame outside evangelical circles — in what Christians call “the World.” He is probably the last member of the church’s staff you would pin for this fate. Among the charismatic showmen at Prestonwood, Bailey is every inch the loveable tech nerd behind the scenes. He wears jeans, running shoes, and a T-shirt under an unbuttoned flannel, with a comms earpiece perennially hooked around the stems of his IT-guy glasses. As the de facto social media manager for Gift of Christmas, he’d won his brief moment in the World’s spotlight accidentally: One of his #churchproduction Instagram posts of a rehearsal of “Little Drummer Boy,” which involves five drummers soaring through the sanctuary on fly-systems while a Pink Floyd-style laser show erupts around them, got picked up first by local news outlets and then eventually landed on the online tabloid Daily Mail.

“My wife kept telling me: Don’t read the comments. Don’t read the comments.”

He read the comments. He didn’t respond to anyone unless they were asking technical questions, in which case he responded immediately, and in detail.

“What I found was that there were three different types of critics. There’s the obvious, ‘tax the church’ critic, which I’m not…” He waves his hand. “They can have those opinions.”

The second kind of critic, he said, was the faith-based version of the first: those who say that the church should only spend its money on helping the poor and needy. Prestonwood knows the optics on all this look bad. Without opening up the books, what they say is this: The total production cost of the show is covered entirely by the sale of tickets. By which they really mean: No money is taken out of the plate to pay for flying drummer boys. With tickets ranging between $19 and $69 (plus a buffet option) and 70,000 tickets sold, I figure the total production costs probably run to about $2.7 million. Staff salaries are not included in this figure, so that money supposedly covers all audio, visual, and lighting rentals, as well as contractor fees for lighting design, fly-systems, graphics, pyrotechnics, animals, costumes, and orchestra players for a two-week-long production that Bailey himself describes as “the largest scale and most technologically advanced show that goes on, certainly during Christmas, maybe ever.”

Let’s agree that it seems pretty clear they’re not turning a profit. For those who argue that the church shouldn’t spend any money on theatrical productions, Prestonwood has a ready answer: The mission of the church is not to feed or clothe as many people as possible, but to share the gospel with as many people as possible. And for that Kingdom Work, Gift of Christmas is perhaps the most profitable investment of all: Bryan claims that every year roughly one thousand people accept Christ after coming to the show.

“Even if just a handful of people came to Christ, that would be awesome,” Bryan continues. “But at some point you have to start weighing — a terrible term — ROI, and the ROI on this show is insane.”

The more stinging criticism for Bryan, then, is not those who take issue with the church’s finances but with its style.

“This one just baffles me,” he says, “and it sounds crazy, and I think it is crazy, but there are believers who think doing things in church with excellence is just not called for. They say it has nothing to do with the money spent or anything like that, but that it’s all just too much. That it’s over the limit. And I don’t even know how to have a conversation with somebody about that, other than to show them the numerous scriptures that seem to point otherwise.”

Bryan’s argument, at its core, is a simple one. If you believe that the God of the universe sent his son to be born on this day 2,000 years ago, to complete a mission that would save humanity from eternal perdition, then how could you possibly justify any celebration of this moment that does not strive to match the splendor of its significance? If God illuminated the night skies over Bethlehem with armies of angels to announce the birth of Christ, then isn’t flying a few from the rafters, if anything, selling it short?

For Bible-based Christians like Bryan, ultimate authority on this question comes from scripture. And while there is no commandment which states that thou shalt parade three saddled dromedaries across a soundstage in celebration of the virgin birth, there is a story found in the gospels that resonates acutely with Prestonwood’s entire ministry. Unlike most stories about Jesus, including his birth, this one is found in some variation in all four gospels, making it uniquely salient for understanding Christ’s true character. In each version, a woman, likely a prostitute (Luke simply calls her “a sinner”), approaches Jesus with an alabaster flask of costly ointment and uses it to wash him (in half the gospels it’s used to wash his head, in the other half she uses her hair to wash his feet). The disciples chastise her: That ointment ought to have been sold and the money given to the poor, rather than wasted in a ceremony that might just as easily be performed with cheaper materials.

“Why do you trouble this woman?” Jesus asks. “She has done a beautiful thing to me. For you will always have the poor with you, but you will not always have me.”

“Please excuse the mess,” Kristin Jimenez says, clearing a rubber cockroach from her desk and replacing it with a Stanley-brand cup covered in Christmas wrapping paper. “It doesn’t always look like this.”

“Oh yes it does,” a voice reprimands loudly from outside the door. “You know it’s a sin to lie, Mrs. Jimenez. Especially to the press.”

“That’s Jill Chatham, my work wife,” Kristin explains. “We do kids worship — on paper. Really what we do is everything unassigned, which is what most of this Christmas show is.”

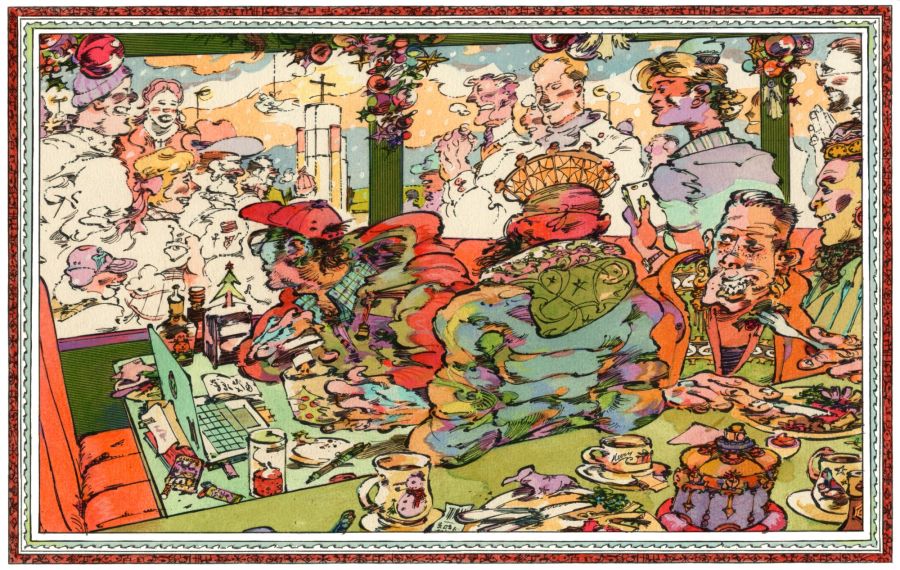

The Gift of Christmas showrunners pride themselves on the grown-up professionalism of their operation, but the fuel of this show is children. Hundreds and hundreds of children. Not only do kids fill out one third of all roles in the show, but it is also their families and relatives and coaches and schoolteachers who fill the remaining seats in the audience on any given night. Nobody explicitly acknowledges this, even though it is plainly obvious, but the entire show is created to appeal to the sensibilities of children — and to the kind of adult who desperately wants to return to childhood.

The burden of making the show kid-friendly falls to Kristin and Jill. Their post is a windowless side-room which lacks the posh leather couches, mounted flatscreens, and reclaimed wood desks of their male colleagues. Instead, their cheap particle-board desks are covered in an assortment of Hobby Lobby decorations and kids’ art supplies, and their chairs look like they’ve been recently rescued from a hellish life in a Sunday-school classroom. “They stuck us over here in Papua New Guinea because we make such a mess,” Jill says. “Most of the props here are handmade, but I won’t lie, we get a lot from Hobby Lobby.”

Jill nods seriously. “They’ve got our form on file.”

Humility is as inextricable from these women’s characters as salt is from the ocean. The “handmade props” they’re referring to are not knock-offs of Hobby Lobby merchandise; they are objects of vastly superior craftsmanship. Rows and rows of them can be found backstage, where at any given moment they are fussed over by half a dozen church ladies. A hot-cocoa stand made from a cocoa mug the size of William Taft’s bathtub; a life-sized roasted chestnut cart, complete with fifty-seven individually wrapped and dyed paper chestnuts; orange shovels covered in white spray foam to resemble snow; a wheeled canvas laundry cart filled with black spray foam to resemble coal.

Mrs. Claus’s bakery trolley is filled with imitation gingerbread houses, cupcakes, cookies, and three-tiered cakes, plus assorted macarons and cream puffs, the whole contraption outlined with what look like hi-vis reflector strips but are actually, upon further inspection, hundreds of imitation peppermints with rhinestones hot-glued on. There is also a wood-framed baby trolley with a polished steel handlebar and red-and-green upholstered bassinet; seventy-two individually wrapped presents, thirty-five cotton snowballs, eight Maplefield typewriters (and eight typed letters to Santa with matching stamped envelopes addressed to “The North Pole”), seven tambourines, four Mjölnir-sized lollipops, three handmade carpenter’s desks, two wicker baskets, and a cornucopia of imitation food: olives, plums, cabbage, grapes, muskmelon, strings of garlic, lemons, apples, pomegranate, seckel pears, cheese, pumpernickel and sourdough loaves, anchovies, mackerel, and speckled bass. The detail on all this so minute it borders on the absurd: Only someone standing within a few feet of Mrs. Claus’s trolley, for example, would notice the hot cocoa mugs have delicate candy-cane straws inside, which one of the church ladies adjusts to ensure they are poking just above the rim.

“The only prop we don’t have is a baby Jesus,” Kristin says as she crouches to rotate a wedding cake so an unsightly patch where a gumdrop has been pried loose from a dollop of meringue won’t face the audience. “I wanted to include a real baby in the show. Ideally, he’d cry on cue. It’d really solidify that He was a human.”

Kristin, who wrote Gift of Christmas’s script and costars as Elisa the Elf, moved to Dallas from New York, where she had spent a handful of years trying out for Broadway shows before a tough season touring with Shen Yun compelled her and her husband, a trumpet player, to return to Dallas and use their gifts at a church. With long, wavy black hair, Kristin stands out like a dark rose among the monotonous blondes of Dallas. And unlike some of the other power players on staff, her eye towards production is not so much polished as weathered — the product of having had a coarse experience in the world that wore her romantic bearings down and left her with certain hard, unvarnished truths about the purpose of performing. She is not cynical but pragmatic. The mark of her pragmatism is woven into the show’s entire structure.

“Before I started, it was more of a musical review,” she explains. “So just kind of this song, and then that song… and none of it really tied together. I think whenever we’re writing, we always have different itches we feel like we need to scratch. We have to get that nostalgic moment. We have to get that romantic moment — well, I should mention that in this show we don’t have a romance moment. Like ever. The whole ‘Santa Baby’ thing, or ‘I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus’… I’m not gonna take the ball for that.”

She laughs. “Anyway, you have all these itches you want to scratch, but I always think things are so much more interesting when there’s a storyline that ties it through. One of my giftings is being able to justify anything. The whole Bible itself is just one big story, and it all ties together. And the more you know the Bible, the more you see how intricate that story is and how deeply it’s all tied. And the more intimate you are with Scripture, the more you can see how intentional every single word is. And I felt like we were missing an opportunity to bring that same intentionality with what we are doing here.”

Kristin’s revised script kept the showstopper songs, but she instilled an undertow of melancholy throughout the holly-jolly first act. The show opens with Santa’s workshop losing power. The world, it seems, is deficient in holiday cheer. You can probably tell the rest of the story from here: It is up to the humble elves, through the awesome power of Andy’s choreography, to raise the needle of the Spirit-o-Meter to pulsating overdrive so that Santa can deliver presents by Christmas morning. But this cliché has a different message in the Gift of Christmas context. The manufactured joy of the elves is difficult to parse from workplace anxiety, and Santa’s entrance — a bombastic rendition of Richard Strauss’s “Thus Spake Zarathustra” that was inspired, Andy told me, by Elvis in Vegas — is clearly mock-heroic, eliciting more pity than pride for this hermetic little polar kingdom. The sheer biomass of performers that accumulate on stage for the act’s finale — a balls-to-the-wall rendition of “Jingle Bells” — is almost frightening: One feels a coercive force must be necessary to hold together this massive display of joy.

As the second act begins, the onlooker has been primed by the spectacle of the first to feel that queer emptiness a secular celebration leaves in its wake, so that when the choir begins singing traditional Christmas carols, he or she feels a keen sense of how paltry fake miracles are when juxtaposed with the real thing.

Like all Prestonwooders, Kristin has no qualms about using secular culture for the sake of Kingdom Work. It’s her job, she says, to consume whatever creative inspiration is out there and refract it through the gospel message. Like Bryan, she has her own grounding in scripture to justify the approach.

“There’s this parable, and it’s about, you know, the creative men of the age. There was this manager, and one of the guys that worked for him was basically robbing his boss’s money. And instead of punishing that guy, he decided to promote him. He said, ‘Listen, if you’re making money for yourself, go make money for me.’ And basically — I’m paraphrasing, like, big time — but basically the heart of the parable is that this man was cunning, and he was cunning in a bad way, but we as Christians should strive to be cunning and creative and figure out different ways to bring the Word of God to people.”

She mulls over her next thought. Few, if any, theologians have ever really understood the parable of the tenants, but Kristin seems to sense that she’s in a unique position to understand why God might want one to bend the rules for the sake of the Kingdom.

“I know that we get a lot of heat for whatever we spend to make the show happen. It’s over the top. It’s extravagant. But so is a Taylor Swift show, and her message isn’t near as exciting as ours. And I just think, ‘Why would we limit ourselves to celebrate a limitless God?’ Right?”

My name is Caroline and I’m from Plano Caroline yes — Caroline yes ma’am I want you to know something yes ma’am I want you to know that someone here nominated you Caroline yes ma’ — someone told us you were having some trouble during this holiday season and yes ma’am my mom my mom — she died and my son my son — he not doing well and he been in the hospital and it has not been easy for me and Caroline yes Caroline I’m calling to tell you that you have been in someone’s prayers and they have been answered here today oh my gosh Caroline KLTY the REAL Christmas station is going to give you $1,000 oh my [weeping] Caroline thank you ma’ — Caroline I want you to know that everything is going to be thank you everything is going to be okay now thank you everything is going to be okay [weeping] Merry Christmas Caroline Merry Christmas.

In pressed tuxedo pants and cream dinner-jacket, Larry Brubaker warms up the choir backstage before opening night. Everyone is mingling, getting settled. Outside, the coaches from distant, lesser churches pull up to the curb with loud pops as air pressure releases to apply the brakes, expelling happy old people who join the crowds of young families: dads in Ducks Unlimited vests and jeans with lycra waistbands, moms with freshly balayaged Mormon curls and acrylic sweaters, little girls in bows and ballet flats, and boys with unruly cowlicks and itchy poplin shirts. Children dart past the old folks like river rapids around boulders.

Backstage, the monitor in the choir room switches from a college football game to a live feed of the sanctuary, which is now filling with the tide of opening night. Seven thousand seats sold out. Fifteen minutes to showtime. The sequins begin to stir.

“Listen,” Larry tells the choir. “You see these name tags down here?” He gestures to a nearby table. “We have a new protocol. You probably saw some things about no backpacks coming in tonight. All we are attempting to do is make things as secure as possible. Okay? Very, very important for our safety and security.”

Steam curls from a fresh cup of coffee, held by a soft, liver-spotted hand. Loud lipstick stains the rim. Another snack-sized bag of Doritos squeals open as people whisper… Security? Whatever from?

“Now I’m sure many of you can’t help but notice the special guest in our room tonight,” Larry says.

Beside Larry, dressed in a fleece vest and collared shirt, a stout man reposes against a foldout table. He’s got a solid crop of silver hair combed straight back; his white smile has the choir ladies swinging their small feet beneath their seats in glee. To 50,000 members across three campuses, and to millions of believers around the world, he is known as Dr. Jack Graham, native son of Arkansas. As a teenager, he heard the call at a little church in Conway and went on to rescue Prestonwood after its founding pastor was disgraced by an extramarital affair, eventually growing the church by 2,000 members annually until it outgrew its original digs and had to upsize in Plano. Since then, he’s served as honorary chairman of the National Day of Prayer, as a member of President Trump’s Religious Advisory Council, and as president of the most powerful evangelical organization in America, the Southern Baptist Convention — twice.

Dr. Jack Graham, in whom He is well pleased. Backstage at Prestonwood, he is simply known as Pastor.

“They say there’s no business like show business, but this ain’t show business. This is God’s business!” Pastor declares. The choir cheers. His voice has the well-oiled suppleness of an old catcher’s mitt; the choir welcomes its embrace.

“You know we have a theme here at Prestonwood, which is excellence at all things. Every song we sing, every line we read, we do it for the glory of God. What does that mean? That means to elevate Him to a rightful place of glory and power and honor. We get to tell this story in a beautiful way, in an excellent way. And I couldn’t be prouder of you.”

Men hold up their phones with two hands, shakily. The Pastor, Dr. Jack Graham.

“We know not every church can do something like this. But to whom much is given, much is required. A lot of people, unfortunately, see the story of Jesus and the Nativity as a children’s story. And yes, children love the story of the Nativity, of the baby Jesus, but it’s the story of the ages, and it’s, it’s… it’s a story that is true. We love to tell this story because it’s true. It’s true.”

Pastor pauses, making patient eye contact around the room, reassuring each member of the choir that he believes the story, too. “That’s the message that we share. That’s our mission. Our mission is the kingdom of God… Our goal, we say around here, is to make His name famous. And we do it in a big, bold, Texas kind of way.”

He’s preaching to the choir, but he can’t help himself — Pastor feels that gospel rising up inside him. God only knows how many times he has shared it in the last half century, to unsuspecting men in barber shops, to anxious wives in grocery-store aisles. And here it is again: God made you but sin broke you, but God so loved you nevertheless that he sent his only begotten Son to die for you on the cross.

“So what do you need to do?” Pastor asks the choir, who have heard it just as many times as he’s preached it, but who lean forward still. “Believe. Believe on the Lord Jesus. Believe, and then you may live.”

Jesus said unto him, If thou canst believe, all things are possible to him that believeth. And straightaway the father of the child cried out, and said with tears, Lord, I believe; help my unbelief.

— Mark 9:23-24

I knew the Gift of Christmas would be a good story. It had everything one might want from an American tale: vanity and excess and ironic juxtaposition, but also zealotry and innocence and unspoiled idealism. Many excellent magazine features begin with a writer trespassing on some unsuspecting utopia, and as Americans — as a people who have inherited so many failed utopias — we derive masochistic pleasure in witnessing a writer unravel a false paradise by turning a mirror upon his subject. It’s the great illusion — and for someone like me, temptation — of this work. Hold the mirror just so, and the world will see the subject as you do.

I called Prestonwood in early September of last year, told them I was a music critic interested in reviewing their show, and asked if they would let me interview some of the key players to give the piece some color. I was not duplicitous. They had the internet. An operation at the scale of Prestonwood — and on this point I have not been exaggerating for effect; ask any evangelical leader, this is a very powerful institution — has ample resources to defend itself against journalists like me. I would not be exploiting generosity. I’d only be penetrating an institution’s lazy sense of invincibility to cut it down to size.

Everything went according to plan, at first. I arrived at Prestonwood on a pleasant Monday afternoon in early December and immediately found myself in friendly company. Larry, the orchestra conductor and my initial point of contact, had told me over the phone that the first thing I’d need to do when I arrived was sit down with the church’s legal department to sign some paperwork about my coverage. Yet, when we met in his office for the first time, he instead shuttled me around so I could get a number of hour-long interviews with cast members before rehearsals began in earnest, apparently forgetting the paperwork. I, in turn, forgot to remind him.

As the week went along I found myself spending upwards of twelve hours a day on Prestonwood’s campus, meeting with cast and crew, and experiencing something novel in this profession: not simply being tolerated, but feeling liked. People offered to take me out to lunch or coffee. Heaping plates of catered dinner always found me backstage. Jill and Kristin set aside room for me to have a makeshift desk near their office space. Bryan even gave me an in-ear comms set so I wouldn’t miss any of the juicy, behind-the-scenes dialogue. At one point, Larry took me on stage while the crew were setting up light displays, and he pointed out all the vantage points he had organized for me to see the play from: down in the pit with the orchestra, backstage in the prop room with the stagehands, up in the rafters with the high-fly crew and the angels. That evening I wrote in my notebook: It’s like he’s directing the whole show for me.

What you read in the first act of this story was the result of those five days: unfettered access to every component of the Gift of Christmas, gained with nothing more than a persistent smile and a clean, tucked-in collared shirt. I hadn’t been in a church like this in almost five years, yet my muscle memory remained. I waved at folks in the parking lot, pressed both hands over the ushers’ when they greeted me, bowed my head like a lamb during prayer. The first time I checked in with the old lady at the front desk I asked her for a mint from her secret stash in a drawer, because, having grown up in church, I knew with crystal certainty that she had a secret stash of mints in her drawer.

Like attending Vans Warped Tour or cooking with Olestra, becoming born-again is a cultural experience that many low- to middle-income Americans share. Roughly forty percent of Americans claim to have had a born-again experience, but of those only about half continue to attend church. The other half sit at bars and laugh about the whole thing with a faraway look of wonder, the way hippies who went on to become Reagan voters might look back upon the sixties. It was obviously all outlandish in retrospect and totally disconnected from the real world, but while you were in it life did seem a little more vivid, a little more alive, you know?

Backsliding after a conversion experience has been common to Americans for a long time. In the late nineteenth century, the psychologist Edwin Diller Starbuck reported that more than eighty percent of all people who had a conversion experience at a revival later claimed to have lost their ardor for faith. Curiously, though, only six percent claimed to have lost faith altogether. A conversion experience, if nothing else, marks a permanent turn in a person, though towards what it is hard for me to say.

My whole childhood was spent earnestly leading others towards the light of Christ — it’s what my name means: candlemaker, bearer of light. The problem was that I never saw that light myself, never felt the touch of His garment, never drank from His cup, never once was surprised by joy. It was doubly worse because I had no excuse. I grew up going to church because my dad was the pastor at that church, and while it was not as big as Prestonwood, it was big enough that I had to worry about people in Dallas recognizing my last name. I heard the same message every week, and every time Dad invited the congregation to pray the salvation prayer with him, I echoed his words, contorting my thoughts into intimations of conviction that I hoped might unlock the enigma of belief. But it never worked.

Instead, as I grew older, I engaged in an increasingly complicated game of make-believe. Despite my own doubts, I was determined to give no one cause to doubt me. In college, other church friends joined fraternities and hooked up with women and stopped going to service. I fasted weekly and stayed a virgin. Then I met an atheist named Christian. We were both student-teachers at a prison that was a far drive from campus, and on our weekly commute we fell into a routine that was by then familiar to me: Christian, the atheist, arguing against the material plausibility of the Biblical worldview; and me, the make-believer, arguing for its truth on the basis of love and beauty. Christian is, to this day, the smartest human I have ever met, and I spent most of those drives listening to him pick apart my arguments in ways that revealed more beauty in the world, more love for its inhabitants, not in spite of its godlessness but precisely because of it. This was never more true than when Christian asked me how I knew I was saved, and I fumbled through an explanation of a moment at church camp when I was 13 and thought I felt the Holy Spirit move inside me while singing a worship song.

“What did it feel like?” he asked.

“Like a tingle up my spine,” I said, sheepishly.

“You mean like an autonomous sensory meridian response? ASMR?” he asked, fascinated. “You know, that happens to me when I listen to Chopin.”

Then, one day while driving back from prison, Christian got saved. It was one of the strangest, most extraordinary things I have ever seen. I don’t really know what happened. We were talking about the etymology of the word dandelion — from the French, dent-de-lion, lion’s tooth — when he went uncharacteristically quiet in the passenger seat. After a few minutes I looked over and saw that he was sobbing. Things happened fast. He needed a Bible. I gave him a Bible. He wanted someone to pray over him. I prayed over him. He wanted to be baptized, and asked if I might baptize him.

A few weeks later we stood waist deep in my father’s baptismal, and in front of a few hundred people I dipped him into the trough and brought him up again. And as the cohesion of the water for a moment enveloped him like a placenta, before breaking into streams over his eyelids, I stood there naked to myself in the realization that there was no virtue in pretending to be someone if no one knows you’re playing make-believe.

I realized that pretending to be someone when no one else knows you’re pretending is just lying, and that by pretending to know I was saved I had precluded any chance of experiencing the real thing. So I stopped lying, and walked out of the church.

I have always liked true Christians, the real born-agains — the ones who went through some shit before they found Christ. They usually have a constitution that’s hardy enough to handle irony. Jill was like that. I could tell by her laugh. It said: “How the hell did a rat bastard like me get saved?” Unlike every other woman I met at Prestonwood, Jill wore a ballcap and T-shirt day and night. She got along better with the gruff animal handlers than the stuffy deacons. She occasionally said “damn.”

And she had that rare thing for a church lady: the ability to make fun of a man. When a debate burst out backstage about the best barbecue in Dallas — about as hotly contested an issue among Prestonwooders as the problem of free will — a man cut in to “settle” the question by saying it was undoubtedly a place that had since closed down, called, “I think, The Pink Pony Club.” Jill exploded in laughter.

“Oh yeah, Jim, I’m sure you loved that barbecue. Was it all you can eat? Open late? D’you have to park ’round back?”

Kristin likewise had the confident air of a woman in charge. (Jill told me no matter what I write, make sure to say that “Kristin does not get enough credit.”) With both of them I felt free to crack wise about the production. We joked about the llama who suddenly went into heat during production having had “the spirit moving in her,” or how the alpaca who unexpectedly gave birth during the show might’ve been a virgin. (Jill: “Nope. I checked.”) None of the showrunners who welcomed me into Prestonwood thought to ask me if I was a believer, but I felt Kristin and Jill were the only two who didn’t assume so. In their case, not asking me the obvious question felt less like naïvety and more like grace.

And that’s what precipitated a crucial journalistic mistake: I got comfortable. It happened on Saturday, my final day at Prestonwood, when the crew was in the middle of a grueling slate of three shows, back-to-back-to-back. I spent the first performance backstage, where in the bustle of things I had forgotten to check in with the front desk to get my daily security pass. It would be fine so long as I stayed close to familiar faces, I reasoned. When the first show finished, I didn’t bother the security team with printing me a new tag since I planned to watch the second show as an ordinary audience member. My judgment was correct: I slid into the front-row seat Larry had reserved for me, and for the first time that week I kept my notebook closed and allowed myself to simply enjoy the show.

Which I did, until the third act began and I felt the imminent approach of Invitation. This is the rub of evangelical Christianity: It is not satisfied by beauty; it is only satisfied by belief. The whole wonder of the show — the kids dancing their hearts out, the old folks singing with hands raised, the candlelight casting everyone’s shadows across the humble manger — meant nothing if you did not believe that the story it told was all literally true. It’s like if Shakespeare came onstage after the opening night of Hamlet and told the audience that everything they just watched was not written to convey truths about human nature but was instead a factual account of Danish history. The imposition did a disservice to the beautiful Judean dude who once told his followers, “If our father’s country were the sky, the birds would belong there more than you. If it were the sea, the fish. But our father’s realm is inside you.”

So while the first angel descended over Mary and Joseph, I got up and left. Since I couldn’t sneak backstage after the show had begun without my tag, I instead hung out awkwardly in the lobby, where Jill was busy wrangling livestock. I took out my notebook and absently scribbled a few notes, and it was shortly thereafter that two barefoot women approached me in their biblicals. They were not smiling. They asked what I was doing, and when I said that I was journaling they asked me about my missing nametag. At this point I noticed a police officer behind them, now looking at me and speaking into his radio. I tried to gesture to Jill, but when I saw that she was distracted by the animals I quickly regurgitated the name of every person I had met at the church, as if the answer to my identity lay in the faith of others. These two weren’t having it.

The older of them asked me what I believed and I started blabbering. It was bad. The words “carbon-14” and “gay rights” came out of my mouth, and not in an intelligent way. No matter what you think, Christians are better at this kind of thing than anyone. They literally train for it. The younger of the two told me she works at some kind of museum “where we show you how science and faith are completely 100 percent compatible.” She invited me to come see her there. She was not not flirting.

After promising the girl I’d come to her museum-thing, where I’d repent and marry her and raise her seventeen kids who doubted the fossil record, I put my head down and walked past the cop towards backstage. I was leaving. No way in hell was I going to stick around for the final show just to face the shitstorm that would descend when information about my apostasy reached the top. Screw journalistic duty. I was going to get in my rental car, crank the volume to Exile on Main St., and drive back to New York that night, stopping at every sleazy dive bar on the way so I could kiss all the patrons on the mouth.

Who on earth was I kidding? I’m not a Christian. I may want to believe in something greater than myself, but I’m damn sure I’ll never be some Hobby Lobby pilgrim worshipping Jesus on a tax-free jumbotron. And the two inquisitors who thought otherwise could get ready to read all about it.

I was expeditiously packing up my desk in Jill and Kristin’s office when there was a knock on the door. Kristin entered. She had just finished the nativity scene and still had her biblical on. She looked serious under her cheap burlap headwrap. We were alone in the room. She said she had to ask me something. She saw my bag packed, and told me it was okay if I said no.

“I think I already know what you’re going to ask.”

She smiled. “Do you want to be in the show?”

My biblical was a plain tunic made of thick upholstery and a maroon, beige, and navy striped sackcloth headwrap. A woman named Iris, who had already spent hours kindly indulging my questions about costume materials — whether a dress was made from silk or organza, whether the down on a pannier skirt was real, whether “pannier” has one “n” or two — had put it together last minute for me at Kristin and Jill’s request. She was excited when she took my measurements in a small backstage utility closet. There was a conspiratorial air about the whole thing.

The final show would start at 7 PM. There was ample time beforehand to write another scene or do a final interview, but instead I stayed glued to my makeshift desk in Jill and Kristin’s windowless office. I did not yet know what had come of my tête-à-tête with the apologists and I had no intention of making myself available for a follow-up. Kristin’s office had a little flatscreen monitor hung in a corner with a live feed of the sanctuary. I sat in my biblical, felt the AC on my bare feet, and watched the pews fill.

C.S. Lewis once wrote that when a young man who has been going to church in a routine way chooses to stop attending he is probably nearer to Christ than he has ever been. I paced the room once the show began, at first in dreaded anticipation of the fateful knock on the door from security, and then, once it was clear my virgin bride had not ratted me out, in fear that I was making the wrong decision. It was fine for me to lie by omission in order to report a story. But this was something different: I was no longer going to pretend to be a believer. I was going to pretend to believe. I wasn’t sure if that was an okay thing for me to do, ethically. Whether holding my candle, singing “Noël,” and gesturing with amazement towards the empty manger wasn’t just a mockery of honest faith. Whether I wasn’t just stepping back into my Dad’s baptismal.

Act Three began, as I knew by heart at this point, with the angel Gabriel floating above heart-weary Mary and Joseph. Ordinarily, this would be the moment when the pilgrims and the animals gathered in the lobby in preparation for the nativity procession, but I was still waiting for Kristin to come get me and was too afraid to go out alone. The angel dipped and rose above Mary and Joseph’s head. The song was coming to a close. The angel was lifted back up into the heavens.

It was then, in my clunky tunic, with my jeans rolled up to my knees Tom Sawyer-style, nervously adjusting and readjusting my headwrap and staring at my unwashed feet on the carpeted floors, that I realized I desperately did not want to be left behind.

The door opened to Kristin’s face, already laughing.

“Are you ready to go to Bethlehem?”

We ran to Bethlehem. Up the stairs, skipping every other step, to a pair of double doors in the upper-level mezzanine. Kristin fished out two candles burned down to the nub from the bottom of a plastic tub. She lit them both and handed one to me.

“This is where I did my first nativity,” she whispered. We were now in the sanctuary, tucked into the shadowed recess of the stairwell, waiting for the first words of “Noël” to cue our entrance. I shuffled in place, the linoleum cold under my feet, hot candle wax dripping on my thumb. My hands were apparently shaking, because the last thing Kristin told me was: “Just hold the flame steady and follow me. Nobody else will know. You’re gonna do great.”

“Noël” is the only song in the show that is performed acapella. When it begins, the stage lights go dark, and the sole source of light comes from the hundreds of candles held by the choir who slowly disperse into the audience, filling the room with both light and sound. As we walked between rows, I saw geriatrics with senile smiles and curious children delighted by fire and the shocked faces of fellow pilgrims who suddenly recognized me under the headwrap. To each of them I sang of how the first Noël was told to poor shepherds as unsuspecting as me.

There’s a story the Spanish existentialist Miguel de Unamuno once told of a priest who could not bring himself to believe. The priest is able to hide this fact from nearly everyone in his village until the end of his life, when an ardent young woman indirectly brings the truth out of him. “Truly, I do not know what is true and what is false, nor what I saw and what I merely dreamt — or rather, what I dreamt and what I merely saw — nor, what I really knew or what I merely believed true,” Unamuno writes. “[But] to have done good, to have feigned good, even in dreams, is something which is not lost.”

“Now point at the peacocks,” Kristin said, leading us up the choir risers. “Now point at the zebra. Now point at the camels. That’s it. You’re doing it, Chandler!”

Heat from the spotlights came down on us. After the magi reached the stage, the choir quit their gesturing and turned together towards the manger. It was time for the final song, the big ticket, the granddaddy of all Christmas carols, “O Holy Night”: written by a French poet who died a bitter socialist; set to music by a vaudeville composer who preferred ballet to church; and translated by an American transcendentalist who intended it to be heard as an abolitionist anthem.

O Holy Night, the stars are brightly shining;

It is the night of the dear Savior’s birth.

Around me the pilgrims transformed themselves one last time into a chorus. The beauty of these next words.

Long lay the world in sin and error pining,

Till He appeared and the soul felt its worth.

I stood on the risers feigning amazement, amazed. Singing, not singing. Pretending, pretending to pretend. Not crying. The crying came later, as I wrote this in the car, under a lonely floodlight in the parking lot.

A thrill of hope — the weary world rejoices;

For yonder breaks a new and glorious morn.

To have done good, to have feigned good, even in dreams.

Fall on your knees. O hear the angel voices.

O night, O night divine.