Bulgarian Puke

The People’s House of Humor and Satire was built by Todor Zhivkov’s daughter, Ludmilla

After eating three or four heaps of the decayed Nazi morphine powder, I felt behind me in the darkness for a handle or lever

The counter system to the counter system will show you both Great Systems in a mirror above the bathroom sink in Gabrovo, where I am washing my balls

PS: The Bogomils were right

Let us ponder the 1980s, geopolitically, economically, and thermodynamically. Ronald Reagan had called the Soviet Union the “Evil Empire” in 1983, though it was an empire so decayed, we would later discover, it barely appeared scary enough to justify another year’s increase to the defense budget. It was a time that would later be called “the height of the Cold War.”

The Soviets were bogged down in Afghanistan, the US was arming the Taliban, and Manhattan, where I lived and worked then, was awash in cocaine and disco. Artists went sour and turned on their patrons. It was the zeitgeist, they said. “I’d sell them shit if I could,” said Andy Warhol, whose gnostic snarl recalls us to the point: Soviet Russia and the Eastern Bloc nations were widely perceived as the great counter system to imperial capitalism, and as Uncle Sam’s rival for the hearts and minds of the third world.

This is all by way of setting the stage for a personal account of my visit to Bulgaria at the height of the Cold War; how I was poisoned by Nazi morphine, nearly smothered in feces, and despite being the civilized representative of a Great Nation founded on Liberty, compelled to wash my balls in a sink.

In the early 1980s I was employed as an editor of a humor magazine with offices in New York City. One day I received a formal invitation, by mail, to attend “the first Biennial Festival of Humor and Satire at the People’s House of Humor and Satire (H&S) in Gabrovo, People’s Republic of Bulgaria,” all-expenses-paid. Paid, that is, as freight-on-board to Sofia International Airport. An invitee would have to provide their own air transportation. I threw that invitation away, only to get another, two years later. Was this fate? Was it a challenge? The call of the great counter system to a humor throwdown at the People’s House of Humor and Satire in Gabrovo?

It could be sold as such, I thought, and explained to my magazine’s publisher that a repeated challenge from the bloc made attendance virtually mandatory and ducking the opportunity shameful, even unpatriotic. “Fuck them,” the publisher said and declined to pay for airfare, though agreeing I might seek it elsewhere.

Securing airfare for a speculative story about a quixotic joust between representatives of the two rival systems of the world, to be held in the dark heart of the Soviet counter system, felt doable. Once I’d explained the situation, another publisher, Malcolm “Capitalist Tool” Forbes, leapt at the opportunity to write me a check.

I was met at the airport by a quasi-official party consisting of a translator, Irina, 20s, young and pretty, but protected from unwanted masculine attention by her pencil-thin mustache and blistering sausage breath, and a driver, Vasil, who worked for the internal directorate of Bulgarian State Security.

Why did a “House of Humor and Satire” exist at all in Bulgaria? Why would the workers and peasants support such frivolous decadence? I learned from Irina the translator that the House of Humor and Satire was the inspiration of Ludmilla Zhivkova, beloved only daughter of Communist Party Chairman Todor Khristov Zhivkov, Bulgaria’s de facto leader from March of 1954 until November of 1989. Tragically, after nursing the People’s House of H&S through its planning and funding stages, but before its completion, Ludmilla succumbed to brain cancer. At her father’s wish, and with his support, the modest cinder-block building in Gabrovo was completed and the festival carried forward in Ludmilla’s memory.

It made me like Chairman Zhivkov that he loved his daughter enough to support her unusual ideas about humor, the Spirit, and fostering world peace. In her final years of life, as well as being a member of the Politburo and holding high state office, Ludmilla Zhivkova became a follower of the Russian theosophist and artist Nicholas Roerich. Balletomanes will recall Roerich — he did the stage and set design for Diaghilev’s production of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring.

Comrade Ludmilla was a long way from a conventional Marxist apparatchik, and the Great Counter System of the world was seeming less like a counter system and more like a back eddy, soon to be sucked into the homogenizing maelstrom of the Great System along with the rest of the world. Ludmilla may not have been an orthodox Marxist or a Marxist at all, but she, like Roerich, was deeply attracted to one of the world’s great spiritual counter systems, Gnosticism.

Bulgaria was home once to Bogomil, a tenth-century neo-Gnostic priest whose followers, persecuted by the Eastern Orthodox and Catholic churches alike, would eventually seed their subversive faith beyond Bulgaria, in northern Italy and southern France, where the Bogos’ sibling sect, the Cathars (aka the Albigenses), can be counted among the wellsprings of the twentieth-century theosophical movement.

That night in Sofia I paid a visit to the New Otani Hotel. Otani being a Japanese luxury hotel brand, which, in a fit of 1980s bank-fueled exuberance, built a traditional Japanese hotel in Sofia, Bulgaria, where no traditional Japanese staff were available. Attention to environmental aesthetics as the foundation of hospitality was a quality of Japanese monoculture untranslatable to the socialist proletariat who made up the New Otani’s local hiring pool.

Beer cans floating; a water garden. Crossing the bamboo bridge. Sideways swimming koi patrol stagnant waters. A Marlboro pack, made locally, under license, rears from green slime.

Upstairs at the New Otani was a low-rollers casino, wherein were found the idle riffraff of a dusty Soviet Bloc entrepôt: bored and belligerent children of ranking officials; government-sponsored gangsters and spies; unwelcoming whores, mercenaries, degenerate diplomats, and hard-eyed arms dealers — anyone in Sofia with US dollars to blow.

“Not true Bulgarians,” Irina the translator insisted. I told Irina the story of a writer, seated in the waiting area of a Chinese restaurant. A cook in a white jacket, wielding a broom, bursts from the kitchen in pursuit of a panicked rat through the waiting area, past a potted ficus, around waiting patrons, eventually driving the rodent out the door and onto Mott Street. Hurrying back to the kitchen, the cook turns to the patrons, gestures with his broom in the direction of the vanished rat, and declares, “Not from here!”

Bulgaria had plenty of rats, local and non, and a well-developed trade in Afghan heroin, gun parts, and jade — in every form of contraband — ably managed for the peasants and workers by the Committee for State Security, Sixth Directorate. Vasil, the driver, worked for a state security directorate normally charged with “Bulgarizing” the Turkish national minority. He’d been seconded to VIP escort duty as reward for harassing Turks. The next day, as Vasil was driving Irina and me to Gabrovo for the official opening of the Festival of H&S, I finished a road dawg of Bulgarian peach brandy and recklessly asked if the Turks were really all that bad?

“Turk are shit, this is known,” said Vasil. Irina nodded doubtfully. “It’s good you have a driver,” said Vasil. “There is death penalty in Bulgaria for drunk driving.”

That evening there was a party at the Writers and Artists’ Club in Gabrovo for all the festival’s guests, who came from Malaysia, from Iraq and Iran, from the fraternal Eastern Bloc countries and African “aligned nations” alike. Aside from myself, the only other festival guest invited from the West was a Brit, an editorial cartoonist from the Guardian, whose powerful images of the Uncle-Sam-as-an-eagle preying on third-world children hung in the entrance hall.

To be clear, the innocuous-seeming Bulgarian peach brandy was playing hell with past and future, mashing time and perception to insidious effect. Under the effects of this potent local liquor, Irina’s skimpy mustache almost disappeared. In the club’s main seating area, Irina pointed out a Haight and Ashbury–looking dude setting up a knock-off Fender Super Reverb amp, and confided this was Bulgaria’s Bob Dylan.

Just as Bulgarian Bob started to play, the power went off. There was some cursing, some flashlights in the darkness. There was more shouting, some ruckus, and a crash before the lights came back on. Bulgarian Bob was shouting. According to Irina, someone had damaged his amp, a mishap for which he blamed the Writers and Artists’ Club management, and he refused to play until a tube in his amp was replaced at the club’s expense; or never, he didn’t care. Irina was too distressed to be clear.

It soon became evident that, for whatever reason, Bulgarian Bob wouldn’t be performing. Irina was embarrassed. I assured her America’s Bob Dylan was also disinclined to perform acoustic sets after famously “going electric.” The club’s manager apologized for the artiste, attributed his departure to temperament, and insisted that Bulgarian Bob’s broken equipment was broken when he arrived. The manager then offered unfettered access to the club’s PA system for homesick drunks to sing patriotic songs in their native tongues. It was time to leave.

“They denounce wealth, they have a horror of the Tsar, they ridicule their superiors, condemn the nobles, and forbid slaves to obey their masters.”

— Cosmas the Priest, Against the Bogomils.

The Bogomils were a sect of Gnostics who settled rural communities, initially in remote mountain regions of Bulgaria and later throughout the Balkans, but away from the cities, official churches, and secular powers. Like the theosophists who attracted Ludmilla Zhivkova, the Bogomils rejected the spiritual systems of the world, all of the exoteric religions of the day. They differed from many earlier Gnostic sects in that they were entirely ascetic: the shocking sex and semen-gobbling rituals of “licentious Gnostics,” their polyamory and sacramental inversions were as meaningless to the Bogos as any other pagan delusions. The Bogomils “preached a stand we have long known: a total refusal to compromise with a damned world contaminated by evil and the devil,” while they were engaged in a “pitiless struggle against the temptations of the body,” according to a sympathetic French author Jacques Lacarrière, in The Gnostics.

The invited representative of The Great System of the World traveled to the Heart of the Great Counter System, found that the Heart of the Great Counter System was itself a Counter-Counter System, and awakened in a Bulgar hotel at 4:30 AM with a terrible hangover determined to seek remedy.

I’ll spare myself the embarrassment of detailing the ruses employed, the implied promises, the insinuated threats, backed by the desperation of a big-city addict. My position was this: an invited guest of Todor Zhivkov with a crippling peach-brandy hangover the host nation was bound to mitigate. A few Vicodin would be fine. This simple request turned out to be less than simple, for while Bulgaria was a major transshipment port for Turkish and Afghan opiates, nothing of the sort was available to civilians. “What do you do,” I demanded of a stonewalling medico, “when party boss breaks his leg? Fob him off with aspirin?”

Eventually, at the main polyclinic, I located a physician who understood my case. After unlocking a series of cabinets, boxes, and drawers she produced an ancient foil strip of tablets. As I studied the black letter Gothic print, I could make out “morphinsulfat” and a swastika. “Very strong,” the Bulgarian sawbones said. “German.” We had minutes to make it to the People’s House of H&S.

Isn’t humor itself Gnostic? Doesn’t it depend for its existence on the shameless hypocrisy and contradictions of all systems? Isn’t a counter-counter system another system-in-waiting with the same flaws, the same weakness, only mirrored? The opening ceremonies at the People’s House of H&S were brutal. We, the invited guests, and a handful of well-behaved peasants and workers, stood in the blazing summer sun listening to general after general, in reverse order of rank, take a turn at the microphone, welcoming us again, “invited guests, workers, and peasants.” The first, least important general, who blocked his hat on a hula hoop, spoke for 25 minutes. Each succeeding general competitively bettered that time.

Across the sweltering street from where we stood, facing a dais full of generals, the shade and shadow of the doorway to the air-conditioned People’s House of H&S, beckoned, so I asked Irina how much longer the ceremony was likely to extend. After counting the generals, she estimated several more hours. It was 94 degrees in the sun. I ripped open the Nazi-surplus morphine pack. The pills therein had long ago turned to granular yellow-white powder. I ate three or four mounds.

When the highest-ranking general, who blocked his hat with a hubcap, concluded his speech we were ushered into the People’s House of H&S. There, our party, consisting of Irina and Vasil and I, was told to await the Chairman’s arrival and prepare for the subsequent exchange of humorous toasts between the two representatives of the world’s contending Great Systems.

Finally inside the People’s House of H&S, we waited about half an hour in air-conditioned comfort, the temperature a clement 75 degrees, when the power went out, the air conditioning shut off, and, being a windowless cinder-block building, it went dark. As the indoor temperature rose, the Nazi morphinsulfat was feeling its strength as yet undecided, after a hiatus of many decades, between inflicting nausea or dysentery. I made my way with all possible speed to the men’s washroom.

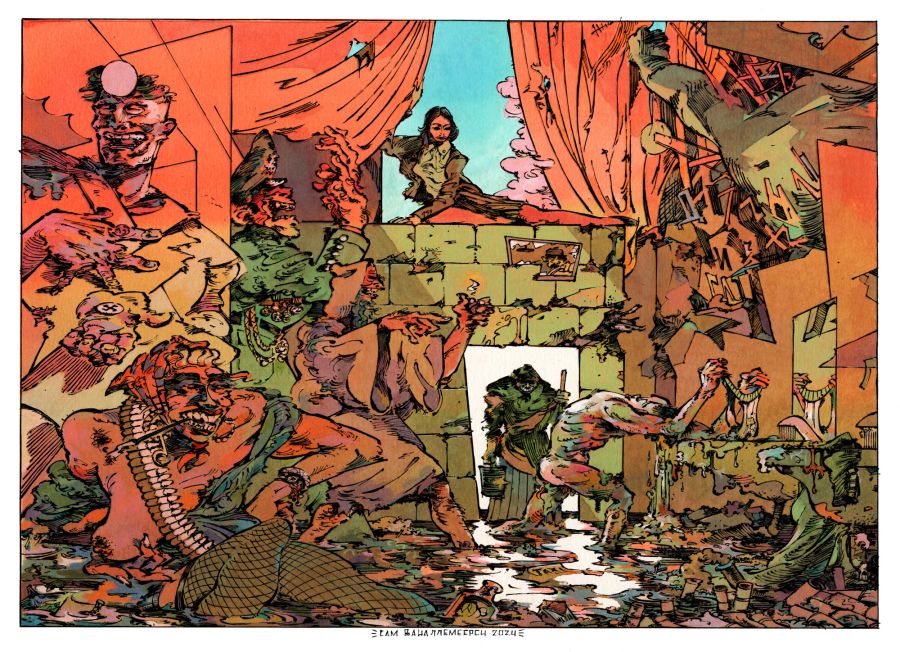

Using a Bic lighter to navigate the dark I passed a row of sinks, walked back to where a rank of cubicles stood. I entered the first open door and vomited into the blackness where I calculated the toilet must be. Having done so, explosive diarrhea declared itself. Dropping my pants, I spun around, attempting to sense with my buttocks the precise location of the vomit-filled toilet bowl, was forced to approximate, and loosed several quarts of putrescent feces at the toilet, which splattered, mostly in the bowl. The humorous toast exchange with the Chairman was imminent.

“You walked in the mud,

And your garments were not soiled,

And you have not been buried in filth.

And you have not been caught.”

— The First Apocalypse of James

What could I possibly do to salvage this situation? I could start by flushing the toilet, so the smell of vomit and feces didn’t permeate my clothes. Step by step, I began to visualize the way out. I felt behind me in the darkness for a handle or lever, but found instead a rope, dangling from a tank above. I pulled the rope, causing seven gallons of water to rush from the overhead tank into the toilet bowl, where it lifted the corrupt mass up out of the toilet, covering the author in his own former contents. Had the Great Counter System defeated the author before the battle was joined? It certainly smelled like it.

Slathered in stercory and flicking the wet Bic, I made my way to the rank of sinks by the door, filled a sink with water, removed all my clothes, and placed them in sink number one to soak while I climbed into sinks two and three and began bathing my body while ducking my head in sink four, a process that involved considerable contortion. Abruptly, the power came back on. I could see myself in the mirror behind the row of sinks in which I was bathing.

At this point the door to the washroom banged open and an old, wizened Bulgarian woman pushing a mop and bucket entered. The heavy-duty custodian barely glanced at me as she made her way back and began cleaning the cubicle I’d defiled. Naked men bathing puke from their bodies in public washroom sinks barely registered, for the old woman was of an age to have witnessed innumerable civil conflicts and two world wars. She had seen the Nazis come and go, had been a victim, and likely victimized others herself. There was nothing new here.

Screw dignity, I told myself. This was a scrap between great metaphysical systems, I reasoned, wringing out my smalls in the sink, and twisting them dry as best I could. Had the Bulgarian State Security poisoned the Nazi morphinsulfat to sabotage my performance in the coming exchange of toasts? Other than making me sick, and perhaps feeding an unproductive paranoia, the Nazi dope had no noticeable (pain relieving) effect at all.

I remember the ceremony. The Chairman, if it was the Chairman and not a ringer, made what struck me as a very Gnostic toast, containing clever references to cultural control systems and zombie ships of state with (I think) the devil in control. Irina was translating, and sick as I was, I laughed several times at the Chairman’s jokes. (The reason for the hesitation about the Chairman’s identity is Vasil’s later suggestion that the “Chairman” was not in fact Todor Zhivkov but a local party official who sometimes doubled for Zhivkov, attending unimportant social rituals.) Vasil, bane of the Turk, made it clear there were few social functions less important than a festival of Humor and Satire in Gabrovo in his, semiofficial, opinion.

I toasted the Chairman, and he toasted me. There was no comic throwdown, ideological or theological. We both made some mild japes at the frailties of the so-called systems we were inhabiting and in our doubleness allegedly representing. I’d like to think that the Chairman and I both recognized our pretended rival economic and political systems as inversions, and therefore as something less than fully real.

If we are scanning the horizon in 2024 for signs of a “paradigm shift,” we will find those in abundance. The rate of change in the rate of change is increasing and this means our future will be nothing like the past. History will be of little use to us. Of course, since we can’t take anything “on faith” anymore, that conception having been eliminated from our normative post-Western discourse, the scale and depth of historical deception will have to be demonstrated, over and over again, in the public sphere, until we are able to see how the past makes the future — until the future unmakes and justifies the past.

Todor Zhivkov died on August 5th, 1998, at the age of 86, from complications of bronchial pneumonia.