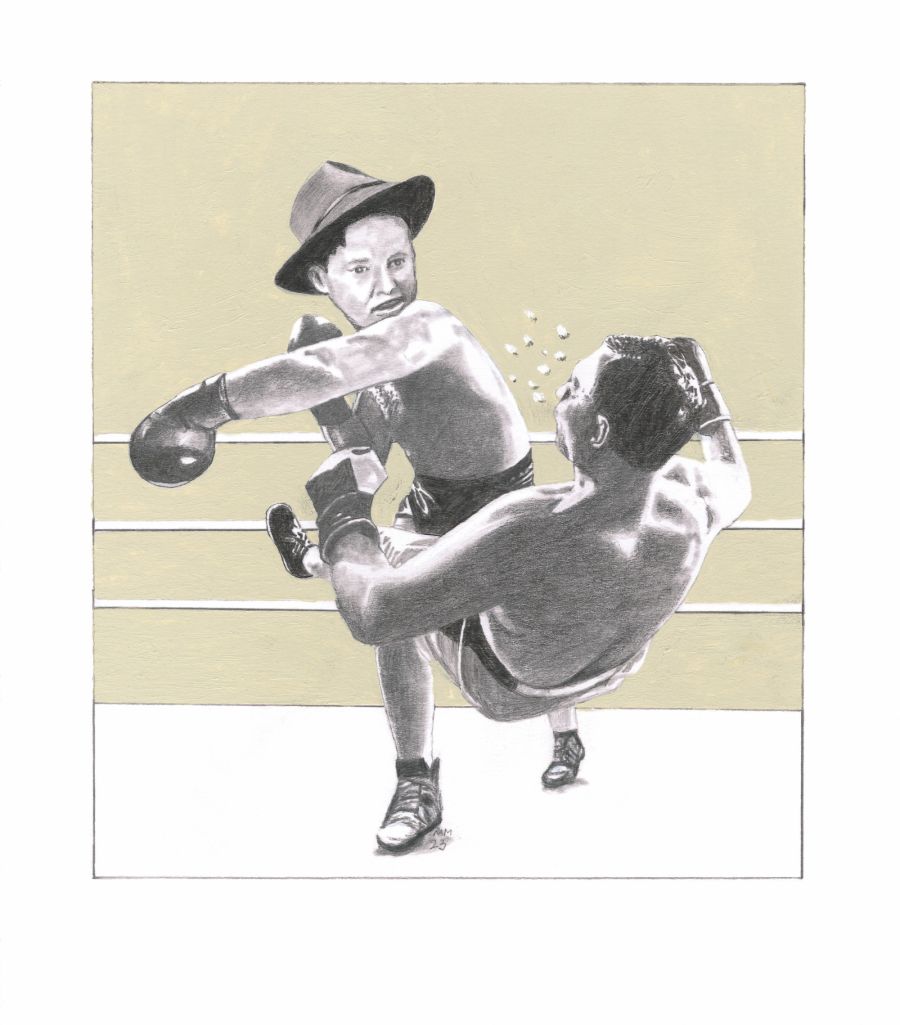

The Cracker Smacker

Fight night in Harlem, where black celebrities bay for white blood in a reversal of the famous scene from Richard Wright’s ‘Black Boy’

Poop in the shower of Mrs. Greenfield’s boarding house

A visit with the Bleeder of Bayonne

Sammy was in his late sixties and he worked the door at Gleason's Gym, which was on 30th Street in Manhattan. That was in the mid 1970s, before the home of great boxing champions like Jake LaMotta, Muhammad Ali, and Roberto Durán migrated to Brooklyn to begin its third life in a new borough, on Water Street.

In the 70s, in Manhattan, Sammy ruled Gleason’s door. Strangers, media representatives, and anyone Sammy didn’t like paid a buck and a half; girlfriends, managers, trainers, fighters, and wingmen were admitted free.

Very few girlfriends applied to Sammy for admittance, though. Gleason’s was a business-like place. Boxers worked out, matchmakers came and went; trainers, occasionally, and managers, inevitably, (still) smoked cigars at ringside. Boxers would train and get out. No one lingered longer than was necessary to decide on somewhere else to meet. The smell of boxers’ hand wraps was that bad. Locker-room wisdom had it strong enough to whip the needle of an old analog stenchometer right across the dial and wrap it three times around the stop pin.

The women who did come to Gleason’s were often leading toddlers or carrying babes-in-arms in search of defaulters in the husband, boyfriend, or baby-daddy category. "He ain't been 'in in a week," Sammy would bark. Later, when the putative father came in, Sammy would screech, "Pay your child support, Camacho, you worthless prick…"

The only time Sammy did business at his tiny box office was when Roberto Durán was inside breaking speed bags, Panamanian narcocorridos blasting from his boom box. On those days, the cops’d block off the street with sawhorses. Fans who couldn’t get inside stood outside, bobbing and weaving, looking for a glimpse of Durán through the open door.

Durán himself, the man writer Budd Schulberg called “a Panamanian street dog,” was managed by “Panamanian sportsman” Carlos Eleta, who owned racetracks, radio and TV stations, and may have inspired a few narcocorridos himself. The media called Eleta a “playboy” when he wasn’t called a “sportsman.” He was sometimes compared to Porfirio Rubirosa, a Dominican tennis player and political assassin of an earlier era. They both liked Italian cars, women, and shoes.

What the Panamanian sportsman saw in the street dog is what brought the fans to fill Sammy’s cash drawer. Homer talks about a hero’s “shining,” a divine aura or glow when a human being is displaced in the body by a god. It’s a unity of body, mind, and Spirit in purpose, and most of us have experienced it on occasion, however briefly, in whatever diminished minor key. Durán had that glow, and he was a street dog, too.

The Scots boxing champion Kenny Buchanan lost his lightweight world title to Durán in 1972, getting hit with a low blow in the 13th round, long seconds after the bell. Durán caught Buchanan’s cup just so, under the lip, and the force of that calculated strike ruptured the Scots fighter’s right testicle. Thirty-five years later, according to George Kimball of the Boston Herald, Buchanan told Durán’s biographer, “I still get a pain there every time I piss. I’ll have it until I die.”

The hypnotic pulse of the speed bags, trainers’ expletives, the boxers’ grunting work, the ancient history of the sport; if it weren't for the stench of hand wraps, it might be almost pleasant. I would note here that a pair of old Roman hand wraps were found, almost perfectly preserved, at an archeological site near Hadrian’s Wall in 2018. News accounts called them “boxing gloves,” but they’re hand wraps, and no doubt still stinking — which is why no one lingers about Gleason’s Gym or Hadrian’s Wall dig sites without cause.

Mrs. Greenfield kept a boarding house in what had formerly been her family home, a well-kept brownstone on a genteel, tree-lined block of 13th Street between 5th and 6th Avenues. With the death of her husband and the estrangement of her grown children, Mrs. Greenfield divided her place into dozens of undersized, quasi-legal apartments. On the top floor, in what he called "the penthouse," lived a heavyweight boxer named Beau Williford from Fayetteville, North Carolina, known to New Jersey club-fighting fans as "the Southern Gentleman," though subsequently billed in Harlem as "the Cracker Smacker."

It was through the influence of the Southern Gentleman with Mrs. Greenfield that I was living in a shoe-box hootch on the fourth floor, where I was awakened one evening by Williford pounding on my door. The boxer had seen the film Rocky, and at age 27, ancient in boxing, he was determined to return to the ring. Toward this end, Williford asked me to go with him to Bayonne, New Jersey, to take counsel with his former boxing stablemate, longtime heavyweight-title contender and hemophiliac Charles Wepner, who owned a bar there.

The New Jersey wiseguys who managed Wepner, Williford, and others ten years earlier had periodically offered their “boys” an opportunity to make some money working a side hustle. One of these illicit operations went wrong and Williford had “gone to college” for much of what might otherwise have been his prime years as a boxer. Meanwhile, Wepner had been christened “the Bayonne Bleeder” by sportswriters after 72 stitches were required to repair his face following a battle with former heavyweight champion Sonny Liston, who could knock a building down. It was not remarkable that Wepner bled so profusely when hit a hundred times in the face by Sonny Liston (as any man would) but that he remained standing for nine rounds despite that beating and, perhaps more miraculously, was still able to count his change in a supermarket long years after.

As Wepner saw it, Williford needed to get into condition, publicly, at Gleason’s Gym. The Southern Gentleman had a spare tire. He needed to do road work. Perhaps chase chickens. He should train with Paddy Colovito and let the matchmakers see him work. Reactivate his boxing license, get his name back in the record books. After that, maybe a title shot for a white contender might open up.

Wepner’s advice had barely begun to flow when a drunken bar patron, who’d played the “Theme From Rocky” four times on the jukebox, interposed himself. Shouldering Williford aside with a “’Scuse me buddy,” the fight fan extended a fat damp hand to Wepner, enthusing, “I just want to shake the hand that knocked that nigger Ali on his ass.”

Wepner jerked his hand away, as the Southern Gentleman said to the fight fan, “Why don’t you shake the foot that helped out, you dumb son of a bitch.“

Back in Manhattan, Williford adopted a mysterious manner as we ascended the stairs of Mrs. Greenfield’s HO-scale apartment building to the third floor and down the worn carpet hallway to the small washroom shared by Mrs. Greenfield’s third-floor tenants. Williford threw open the washroom door and pointed to a sign prominently posted on the translucent shower door. Printed in Mrs. Greenfield’s angry felt-marker capitals, it read:

"WE KNOW WHO YOU ARE.

WE KNOW WHAT YOU’RE DOING.

IF IT DOESN’T STOP, YOU’LL BE

EVICTED.

Signed,

Mrs. J. Greenfield, Owner"

I asked Williford what the drama was about.

"The sick bastard in #306 has been shitting in the shower," Williford confided, adding, "I helped Mrs. Greenfield make the sign."

Williford continued in this vein as we climbed the stairs. How lucky I was to live on the fourth floor rather than the third, and how he assumed I’d find it as funny as he did, even though I still shared a shower with other residents of the fourth floor, which thankfully was not the third floor. And didn’t the Southern Gentleman’s penthouse have its own private washroom facilities where no psycho could break in and shit..?

Williford’s musing on this subject was interrupted by the slamming of my fourth-floor door.

With Williford in training, we looked for a tune-up fight. The matchmaker for an elite Harlem nightclub came to Gleason’s seeking an opponent for an exhibition match he was promoting in his uptown carpet joint. Black celebrities of the day, entertainers, politicians, musicians, judges, and gangsters were the patrons of this famous members-only club, which was noted far and wide for its neatly uniformed, entirely white serving staff. For fight night, the slots and wheels were stored away behind rollaway panels and the craps tables folded up invisibly behind wall-length purple drapes. The whores would wear their best jewelry, and the only betting allowed was on human beings.

Naturally, the Saturday fight night Harlem club crowd being black, the club’s matchmaker preferred Caucasoid opponents. In New York State Boxing Commission-sanctioned exhibition boxing events, just as in Richard Wright’s fine book Black Boy, promoters are not above exploiting common prejudice (or tribal sentiment) for economic gain. The matchmaker’s fighter was, he insisted, “a seasoned pro.” In reality, the boxer in question had won a few fights against other tomato cans back in the day, and when in his prime, he might have been a tomato can himself — his prime having expired 20 years ago.

The matchmaker wanted a white opponent who understood, without any explicit statement or instructions, the role of the white fighter matched with a black opponent in a Harlem nightclub full of drunk black celebrities. “Williford is a seasoned pro himself,” I assured the matchmaker. “He understands the crowd dynamics, and a promoter’s need to make a buck and not incite a riot and wreck the place.”

The matchmaker nodded skeptically and moved off toward the ring to watch Williford spar.

“Whatever he saw, he found reassuring,” I told Williford later. “Or he thinks you’re smart enough not to knock his boy out, even if you can,” I added.

The matchmaker’s contract stipulated a total payment of $750 for a three-round exhibition fight with $200 in advance, with the ref’s decision, as always, being final. Studying the contract on the sidewalk outside Gleason’s, Williford and I slowly made our way toward the subway. Paddy Colovito, the Southern Gentleman’s legendary trainer, ran out of Gleason’s Gym to catch us at the end of the block.

“What are you doing tonight?” Colovito demanded of his fighter.

“Maybe see my girlfriend,“ said Williford.

“You fight tomorrow night! What the fuck is wrong with you? NO SEX!”

“I’ll just get a blow job then,” said Williford, and Colovito howled, “Noooooo, that’s the worst thing you can do — it kills the knees!”

Fight night was a hot summer Saturday in Harlem. The elite club was packed with famous faces, and the limos were double- and triple-parked outside when the Southern Gentleman and his entourage arrived by Checker Cab and were quickly ushered up the servant’s elevator and back to the dressing-room area. It’s been a while since I read Richard Wright’s Black Boy, or maybe only the often-excerpted boxing scene in Chapter 12, where, as memory has it, a crowd of drunk white men emitting billows of cigar smoke screamed at unwilling young black fighters, howling for blood in grotesque parasexual excitement. A typical fight crowd, really, but also, in Wright’s compelling depiction, sickening and racist.

Exhibition fights are not taken seriously, even by the state commissioners who are supposed to regulate them. The profits to be had are small, and the standards, procedures, and protocols are correspondingly flexible. Opponents can be contracted on short notice, and promoters can grab a dollar. Williford was dressed for the fight when the matchmaker arrived with bad news: The “tomato can” Williford had been booked to fight had done a runner, absconding with (the matchmaker claimed) his $500 advance.

The matchmaker had, however, at the very last moment, found a stand-in tomato can who’d agreed to fight Williford on four hours’ notice under the original boxer’s name. This proposed opponent, who shall be nameless, was no starving, dark-horse mauler brought in a Kevlar cage from Guyana. He was a flat-out bum, an ex-fighter who didn’t have much when he had it, and he lost it a long time ago. The opponent had no license, no current medical, and no chance of passing an opiate piss test. Our opponent was not even a tomato can. His ability to make it look like a fight was in question.

It was fight him or walk home to Mrs. Greenfield’s. There was no alternative. There were no overt or covert understandings to be had. We all knew the score. Though most of the patrons did not. The nameless substitute fighter was an imposter, an actual junkie recruited from the block by the smooth-dog matchmaker, a man, it was now clear, possessed of subterranean ethical standards.

Williford agreed to fight the pathetic ringer but insisted the referee introduce him not as “the Southern Gentleman” but as “the Cracker Smacker.”

The crowd booed the Cracker Smacker even before he was introduced. They cheered the imposter, though they wouldn’t give the poor bastard a dollar if he asked for one on the street. Williford “put on a show.” He couldn’t hit the opponent at all for fear he’d fall out of the ring and hurt himself. For two rounds, Williford covered up, and the crowd roared as the faux fighter battered the Cracker Smacker with flurries of feeble punches before halting, gasping, out of breath, punched-out arms hanging like swim noodles at his sides. Williford only threw himself to the canvas once. It was shit work for a real boxer. Which may explain why, in the third round, Williford knocked his opponent to the canvas thrice, helping him to his feet afterward on each occasion, assuring him it was a slip, an accident, a mistake, that it wouldn’t happen again, except it did, three times.

The fight was over. The judges had it unanimous on all three scorecards. The Cracker Smacker had been defeated. The crowd cheered, and the ref raised the victor’s arm and led him around the ring.

The matchmaker had taped $200 in an envelope to the mirror in Williford’s dressing room, with it a note saying that two bills was all he could afford as the runaway opponent stole his $500 advance, reducing the total purse money available. What with the cost of the promotion expenses, securing a last-minute replacement — sure you understand, yada yada, yours sincerely, the matchmaker.

This hoary dimwit ruse required our making a personal visit to the matchmaker’s Naugahyde-wallpapered office. He was reluctant to pay the remaining $550 stipulated in the exhibition-fight contract, adding, “You never fought the contracted guy, you fought a much easier fight, and then, some might say, you made a farce of the fight.”

The matchmaker studied Williford’s face, appreciated the boxer’s determination, and added, "Others would disagree. What the hell. It’s not like I’m gonna pay the other guy."